It’s March 24. It’s World Tuberculosis Day. It’s about nine million. And it’s about three million. Human beings. Human lives.

Every year 9 million human beings get infected with tuberculosis (TB). And three million people don’t get the care they need.

TB is an infectious disease, transmitted from person to person via droplets from the throat and lungs of people with the active respiratory disease, and caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which most commonly affects the lungs.

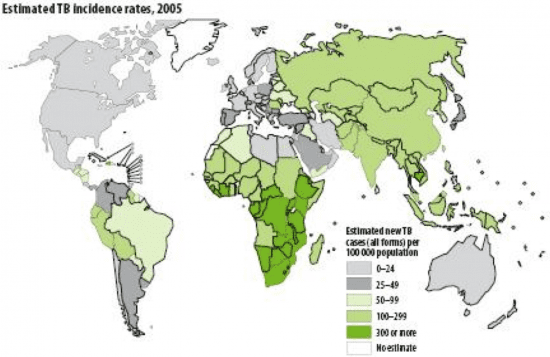

Infectious diseases account for 43% of the global health burden, according to the Global Burden of Disease study by the WHO. In 2004, TB was responsible for 2.5% of global mortality and 2.2% of global burden of disease with more severe impact in low- and middle-income countries.

- In Africa alone there are 430,000 TB deaths.

- Globally, there are 2.8 million new TB cases and 30% of them are in Africa.

- 37% of incident TB cases were HIV positive.

These few numbers tell the story that the current TB disease burden is enormous. TB ranks among the 10 most fatal and disabling diseases worldwide. The world would be a better place if high-impact measures to prevent it and to enhance interventions and treatment were in place.

Those high-impact measures come out of the alcohol policy toolbox. The reason is simple and rooted in evidence: Alcohol use is a risk factor for TB. About 10% of the TB cases globally are attributable to alcohol.

- The prevalence of alcohol use and/ or alcohol use disorder is markedly higher in TB patients than in the general population;

- The prevalence of TB among persons with an alcohol use disorder is also elevated;

- The risk of active TB is substantially elevated in people who use more alcohol than 40g per day, and/or have an alcohol use disorder.

- Alcohol use also exacerbates the progression of the disease.

Numerous studies show the pathogenic impact of alcohol on the immune system causing susceptibility to TB among heavy users. In addition, there are potential social pathways linking alcohol use disorder and TB. Heavy alcohol use strongly influences both the incidence and the outcome of the disease and was found to be linked to altered pharmacokinetics of medicines used in treatment of TB, social marginalization and drift, higher rate of re-infection, higher rate of treatment defaults and development of drug-resistant forms of TB.

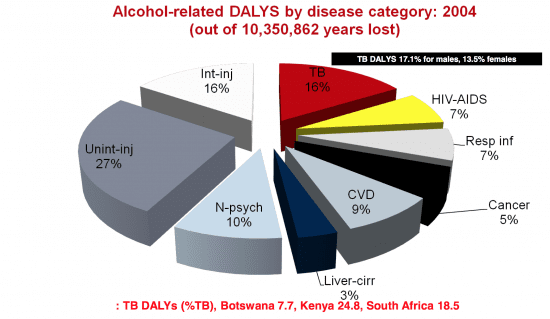

Quantifying impact of alcohol on TB incidence & disease progression in WHO Africa Region (Rehm et al., 2009)

Alcohol is no ordinary commodity. It’s causally linked to tuberculosis and is as such one of the biggest health hazards on earth, being a risk factor for HIV/ Aids, violence against women, and non-communicable diseases.

So, let me briefly summarise:

- Epidemiological and other evidence shows that alcohol use and alcohol use disorder constitute a risk factor for incidence and re-infection of TB.

- Additionally, the course of the disease is worsened by alcohol use.

- Interventions to reduce the impact of alcohol on TB should be considered as a matter of priority.

- With such high rates of TB/HIV co-morbidity these issues need to be jointly considered.

The implications resulting from these four insights for policy responses are clear and evidence-based:

Alcohol exposure at the population level should be reduced by high-impact, evidence-based policy measures, such as measures decreasing the availability, decreasing the affordability and banning alcohol advertising and sponsoring.

—

For further reading:

Rehm, J. et al (2009), The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders, and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 9, 450

Research article: Alcohol use as a risk factor for tuberculosis – a systematic review, by Knut Lönnroth*, Brian G Williams, Stephanie Stadlin, Ernesto Jaramillo and Christopher Dye

Alcohol Exacerbates Murine Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Carol M. Mason, Elizabeth Dobard, and Steve Nelson et al

PEPFAR Southern & Eastern Africa Technical Consultation on Alcohol & HIV Prevention – Windhoek, 12-14 April 2011, by Prof Charles Parry: “Alcohol use and TB”

can I drink some alcohol after dots