Teach your children well

It is hard for children of parents with alcohol problems, this we know, but how is it for children of parents who consume too much alcohol and are not aware that they have a problem?

Their parents’ hell

My ex-husband and I drank a bottle of wine every evening, sometimes more. We regarded it as normal, a way to relax after a hard day. My ex would consume the lion’s share, telling me that the male constitution could cope with larger amounts than that of a woman. We would take a break from drinking wine for a few weeks, but easily slid back into our accustomed routine.

How it all began

I started using cider when I was thirteen, not often, but it was a start. I first got really drunk on Bloody Marys when I was fifteen. It was the first Christmas after my father had died and I had become an orphan, my mother having died when I was one year old. I was supposed to be going to midnight mass with the family who were taking care of me but I ended-up in the local pub with a group of adult friends. They plied me with this alcoholic beverage, telling me it was tomato juice and, before I knew it, I was completely inebriated.

Colluding adults

Although the legal age for consuming alcohol in England was eighteen, many parents thought it was a good idea to introduce their teenage children to alcohol in the ‘safe’ environment of their own home. It was not unusual to be offered a glass of sherry before dinner. From age seventeen to eighteen I was having vodka and orange juice every evening, with more emphasis on the vodka content. I thought nothing of it. I could hold my alcohol intake and people around me were imbibing it too. It was ‘normal’.

My abuse of alcohol continued at university. There was a student bar open at lunchtime and in the evenings and there were regular parties where almost everyone got drunk.

The colluding workplace

I continued during my working life. At the BBC, where I started out, there was a bar and a restaurant in every building. There was many a liquid lunch at a local pub, too. The corporation even had their own brand of champagne, and a drying-out clinic for their staff.

In New York it was no different. Clubbing till the early hours of the morning, champagne with the boss at work on a Friday afternoon, and it still never occurred to me that this might be problematic. Often on a Friday morning I would arrive at work to find a young man sleeping off his hangover on the sofa which my boss had in his office.

Every Thursday evening the young stockbrokers would take their clients out and wine and dine them until the early hours of the morning. This was expected of them and an essential part of their job.

The damage starts to show

I didn’t consume any alcohol when I was expecting each of my three sons, but I continued afterwards and they grew up seeing their parents and friends consuming in the evenings and at lunch parties.

It was only after I stopped using alcohol that I realised that many of the fights I had had with my ex-husband had been fuelled by alcohol. It wasn’t the only cause, but it certainly exacerbated the difficulties we already had in our relationship. We weren’t full-blown people with alcohol problems; at least we didn’t see ourselves as such. People with alcohol problems were other people, those whose lives were out of control. We held our lives together, were comfortable financially and did the best we could as parents. Luckily our sons have turned out to be well-adjusted and successful in spite of going through some tough times.

The longer term effects

I am not qualified to write about alcohol use disorder from a medical point of view but I have discovered that it manifests in varying degrees like, for example, depression which can vary from mild to extreme.

Which is worse?

The children of severely afflicted parents with alcohol problems can see the symptoms and results clearly and it is hard enough for them. I wonder though, is it any easier for those with parents who use alcohol heavily but who still function in society and whose behaviour is regarded as acceptable? An invisible problem can be more difficult to deal with than an obvious one.

How can people in recovery convince their grown children of the dangers?

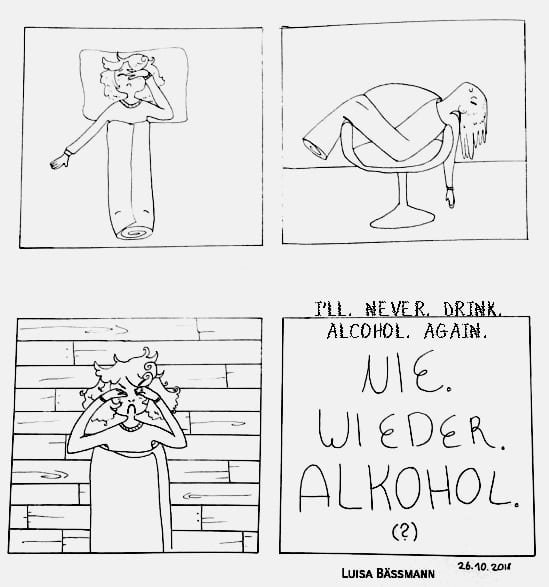

Still, the other day I called one of my sons and he told me he couldn’t talk right now because he had a really bad hangover. All three have witnessed my struggles in the past and are glad that I am ‘dry’, but I can’t get through to them just how dangerous the consumption of alcohol is.

I know that there is nothing I can do for them until they realise themselves that this can be extremely harmful, physically and psychologically. Anything I say will be seen as preaching. I know how reluctant I was to admit that I had a problem. I would go into complete denial and be defensive. So when my son told me he had a hangover, I treated it with humour, saying what a shame he’d wasted a whole day, and think of all the great things he could have done rather than lying around nursing a bad headache. He laughed and agreed with me and it opened up the possibility for a brief and open discussion.

Teach your children by example

The best I can do is to be vigilant but not interfering and be there for my sons when they need me. I was not the best example for them when they were growing up and I can’t undo that, but I can provide an example now. I hope, too, that those who have fought and conquered the invisible or visible problem will also put the past behind them and gently guide their children towards a healthy, happy and sober life.