This guest expert opinion is written by Michael Thorn, former Chief Executive of the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education. An earlier version of this article was published on Croakey on July 30, 2020.

Is it possible that one of the less effective public health innovations to reduce alcohol harm might also be the most important? Might it be better that public health advocates first concentrate their efforts on health warning labels rather than the traditional policy interventions on price, availability and marketing? Recent developments in Europe and in Australasia point towards this being the case.

The placement of government warning labels about the health risks on everyday consumer products is commonplace around the world.”

Michael Thorn

Public health advocates acknowledge warning labels on alcohol products have only a modest impact on alcohol consumption but argue that consumers have a right to know about the harm it causes. What is not discussed is the transformative importance of health warnings in the ongoing effort to implement more effective evidenced-based alcohol control policies that have been proven to prevent and reduce harm – price increases, availability limits and marketing restrictions.

The placement of government warning labels about the health risks on everyday consumer products is commonplace around the world. Warnings on food, pharmaceuticals and children’s toys are familiar to consumers and well recognised as good public health practice. These have been shown to be effective in raising awareness, changing behaviour and reducing harm.

Graphic health warnings on tobacco products have been a significant factor in reducing rates of smoking by raising public awareness about the dangers of tobacco and sensitising the public to other and stronger policy interventions.

This is not to suggest convincing governments to mandate warnings on alcohol is easy. It is not. It takes time.

It took nearly 25 years for Australian and New Zealand public health advocates to secure a mandatory alcohol and pregnancy warning label on all alcohol products when in July 2020 governments agreed to a modest proposal by Food Standards Australia and New Zealand (FSANZ). The alcohol industry had fought this all the way.

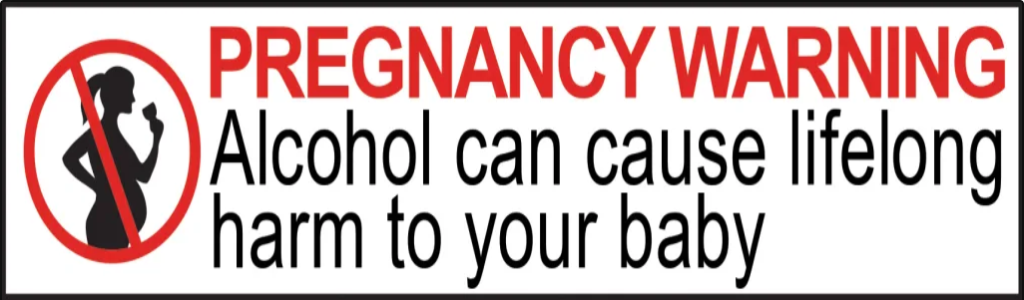

When pregnancy labelling comes into effect in 2023 it will represent the highest standard in the world for a label of this kind – albeit it was a low bar.

While less than optimal – the label should be larger, placement shouldn’t be left to the discretion of producers and the use of the heading ‘Pregnancy Warning’ instead of ‘Health Warning’ means it will have less visual impact – it opens the door for Australasian health advocates to press for a comprehensive alcohol health warning labelling regime.

Persistence, Persistence, Persistence

Like all preventative health initiatives, this measure’s progress has been heart-breakingly slow. The delays have been inexcusable, and the ridiculous three-year implementation timeframe exposes another quarter of a million pregnancies to alcohol.

In his 2011 review report of Australian and New Zealand foods standards former Australian Health Minister Dr Neal Blewett recommended the mandating of a pregnancy warning label. This has been frustrated by alcohol industry opposition and the hesitancy of too many governments, irrespective of their political persuasion. Only the action by the Western Australian Health Minister Roger Cook in October 2018 to force the issue at the Forum on Food Regulation (FoFR) finally set things on a course to enact Blewett’s recommendation.

History shows public health reforms come slowly. Too many sailors died because of the reluctance of the British Admiralty to provision ships with vitamin C to prevent scurvy and it took years for London’s authorities to accept Dr Snow’s 1854 discovery that contaminated drinking water and not ‘miasma’ was responsible for cholera infections.

But perhaps the more terrible example has been smoking where the link between tobacco and cancer was resisted for decades by the tobacco industry and governments (and continues to be in some parts of the world) at the cost of millions of lives.

In this case the three ‘Ps’ of public health – persistence, persistence and persistence – eventually paid off. It took 24 years – from New Zealand lodging an application with FSANZ’s predecessor in 1996 until the eventual decision in July 2020.

Alcohol Industry Interference, Obstruction, and Delay Tactics

In this period came Blewett’s review, a decision by the food ministers in December 2011 to accept his recommendation, and then another nine years to adopt a clear standard.

This nine-year period was characterised by reprehensible prevarication, weak leadership and the usual rubbish from the alcohol industry about costs, false evidentiary claims and brazen bullying of the political class. We also learned of secret talks between the alcohol industry and Commonwealth health officials that saw a dangerously misleading public education campaign by the industry’s public relations agency DrinkWise and witnessed a near-complete failure by the alcohol industry to even apply its own weak consumer messages to containers.

Over this period public health stood tall with copybook and persistent campaigning. Led by the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and ably supported by parents, carers, health, medical and children’s groups, the campaign involved detailed policy development and submissions to parliamentary inquiries, vigorous government relations, endless letter-writing, traditional and social media promotions and regular community attitudes surveys. The essential grist of public health advocacy.

A nine-year period was characterised by the usual rubbish from the alcohol industry about costs, false evidentiary claims and brazen bullying of the political class.”

Michael Thorn

The campaign was never allowed to die, and every effort was made to link this policy to the development of a national fetal alcohol strategic plan, public awareness campaigns about the risk of consuming alcohol during pregnancy and the social and economic needs of children affected by alcohol in-utero.

Trailblazing: Advocacy Should Build on The Landmark Labelling Decisions

Mandated pregnancy warning labels are not new. The United States has required them since 1989, France adopted the pregnancy silhouette infographic many years ago and a recent WHO Europe report showed many former Soviet bloc countries have legislated for alcohol health warnings to be introduced over the next few years, though too often without specifying what they will be.

The Australian and New Zealand decision in setting a design standard for the label specifying size, colour and wording is internationally important and should be copied in other jurisdictions. This will limit the ability of the alcohol industry to minimise the visual impact of the warning.

Although the compromises made – particularly abandoning the explicit ‘Health Warning’ heading terminology with ‘Pregnancy Warning’ (the label isn’t a warning about pregnancy) – will diminish the effectiveness of this alcohol and pregnancy label, it is certainly a quantum improvement on the alcohol industry’s confusing information labels.

A government instigated regime of generic health warning labels will inevitably lead to greater public support for a range of other alcohol policy solutions.”

Michael Thorn

It is abundantly clear from the work in tobacco control that government health warnings are an important pillar in the fight against smoking-related death and disease. It will be the same for alcohol. Such warnings need to be visually prominent, modelled on anti-smoking labelling and include a range of consumer-tested revolving alcohol and health messages, and mandated rules about placement. Blewett had recommended in his 2011 report that governments investigate the adoption of generic health warnings for all alcohol products (Recommendation 24).

The alcohol industry expects this to happen, which is why in Australia and New Zealand they have vigorously fought to delay the pregnancy labelling requirement and the future prospect of the imposition of health warning labels on all alcohol products.

It is also likely that they know that a government instigated regime of generic health warning labels will inevitably lead to greater public support for a range of other alcohol policy interventions on price, availability and marketing.

Public health advocates need to understand this and give higher priority to campaigning for health warning labels. Doing so will help achieve other critical policy interventions.

About Our Guest Expert

Michael Thorn

Michael was the Chief Executive of the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education from 2011 until 2019.

Previously he was an adviser to Western Australian Health Minister from 1988 until 1993 and a senior executive at the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet from 2009 until 2011. He continues to be a consultant and adviser on preventive health.

You can follow Michael on Twitter: @MichaelTThorn