A new study “A narrative review of alcohol consumption as a risk factor for global burden of disease” provides an updated overview on the main results of Comparative Risk Assessment for alcohol consumption. It sketches out new trends and developments, and draws implications for future research and policy.

Abstract

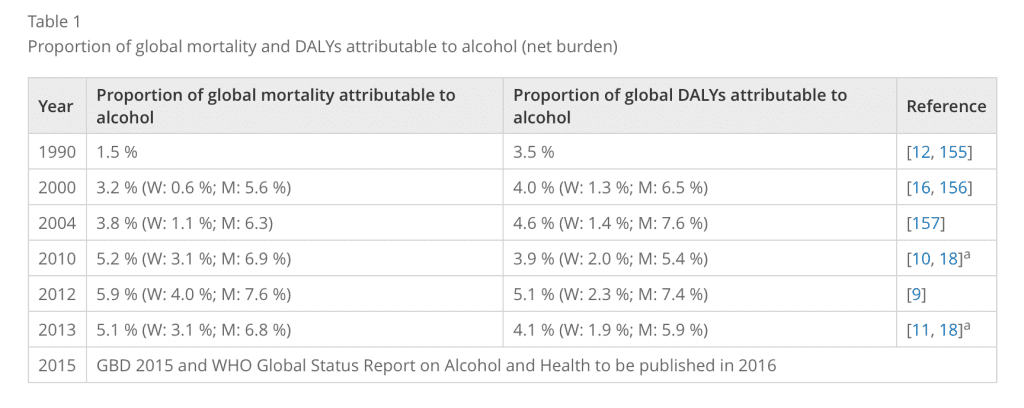

Since the original Comparative Risk Assessment (CRA) for alcohol consumption as part of the Global Burden of Disease Study for 1990, there had been regular updates of CRAs for alcohol from the World Health Organization and/or the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

These studies have become more and more refined with respect to establishing causality between dimensions of alcohol consumption and different disease and mortality (cause of death) outcomes, refining risk relations, and improving the methodology for estimating exposure and alcohol-attributable burden.

Implications for alcohol policy

As indicated above, all CRAs resulted in marked burden of disease caused by alcohol consumption. Two dimensions were identified as important to cause harm:

- Overall level of consumption and

- Patterns of alcohol use.

Policies need to address both dimensions.

There are effective and cost-effective policies to lower overall levels of consumption in societies, such as the so-called ‘best buys’:

- Increase of taxation leading to increases in price of alcoholic beverages;

- Decrease in availability, and

- Ban of marketing and advertisement.

However, these policies do not to seem to be too popular with governments, and in fact alcohol has become more available and affordable in most parts of the world over the past decades (e.g., in the European Union). Other potential ways to decrease overall levels of alcohol consumption would be a decrease in alcoholic strength, which is technically possible for all beverages, and which could be achieved via government regulation, taxation or industry initiatives. It should be noted however, that a reduction in overall level of alcohol consumption does not necessarily mean a reduction in total alcohol-attributable mortality or burden of disease, as monitoring of the last 25 years for the WHO European Region has shown. In addition, it has to be assured, that the heaviest alcohol users do not increase their alcohol intake (e.g., via treatment), and that patterns of alcohol use do not get worse.

Regarding patterns of alcohol use, there are other promising policies such as minimum pricing, and specific policies to decrease heavy alcohol intake occasions in certain situations, such as in participation in traffic or while operating machinery at the workplace. Obviously, harm would be minimized, if in such situations abstinence was the norm.

Finally, the composition of alcohol-attributable burden of disease and mortality will have different implications for policy. A high proportion of traffic injury could be reduced with specific measures for driving under the influence of alcohol, such as introduction and enforcement of a per se law regarding blood alcohol concentration, or reduction of the blood alcohol concentration threshold in existing laws.

On the other hand, high alcohol-attributable intentional injury will demand specific measures such as measures against binge alcohol intake or per se laws on criminal prosecution.

To give one final example concerning chronic disease: high levels of alcohol-attributable liver disease mortality point to high overall levels of consumption, or to relatively high levels of consumption combined with other etiological factors for liver disease such as HIV (as even comparatively small levels of alcohol consumption may cause liver mortality in people with liver cirrhosis no matter which etiology – see above for further detail and, for examples). Reductions of overall alcohol consumption, no matter how achieved, will lead to reductions in alcohol-attributable liver mortality.

Conclusions

The CRA methodology has been evolving and for comparisons over time it is necessary to use the latest methodology and calculate backwards using the same methodology. If this principle is used, then CRAs can potentially inform the health policy process and yield important information for decision makers.

Obviously, interventions will depend not only on the size and shape of the burden, but also on how much of the alcohol-attributable burden is avoidable, and on aspects on feasibility, costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions. For alcohol consumption, in principle all of the burden is avoidable, but any intervention will have to take into consideration the role alcohol has been playing in our society for thousands of years. However, despite these general limitations, information about attributable burden will also be one major building block towards better policies.

—

Citation

Rehm and Imtiaz: A narrative review of alcohol consumption as a risk factor for global burden of disease, in: Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy (2016) 11:37 DOI 10.1186/s13011-016-0081-2 (PDF)