World Bank: Alcohol Taxes for Universal Health Coverage

A new World Bank Group report entitled “High-Performance Health Financing for Universal Health Coverage – Driving Sustainable, Inclusive Growth in the 21st Century” clearly highlights the important role of alcohol (and other health promotion) taxation for achieving universal health coverage (UHC).

UHC is central not only to SDG3 but to the entire Agenda 2030 for sustainable development and too many countries are currently leaving too many people uncovered and vulnerable to poverty, ill-health and marginalization due to catastrophic health spending and health risks.

Executive summary

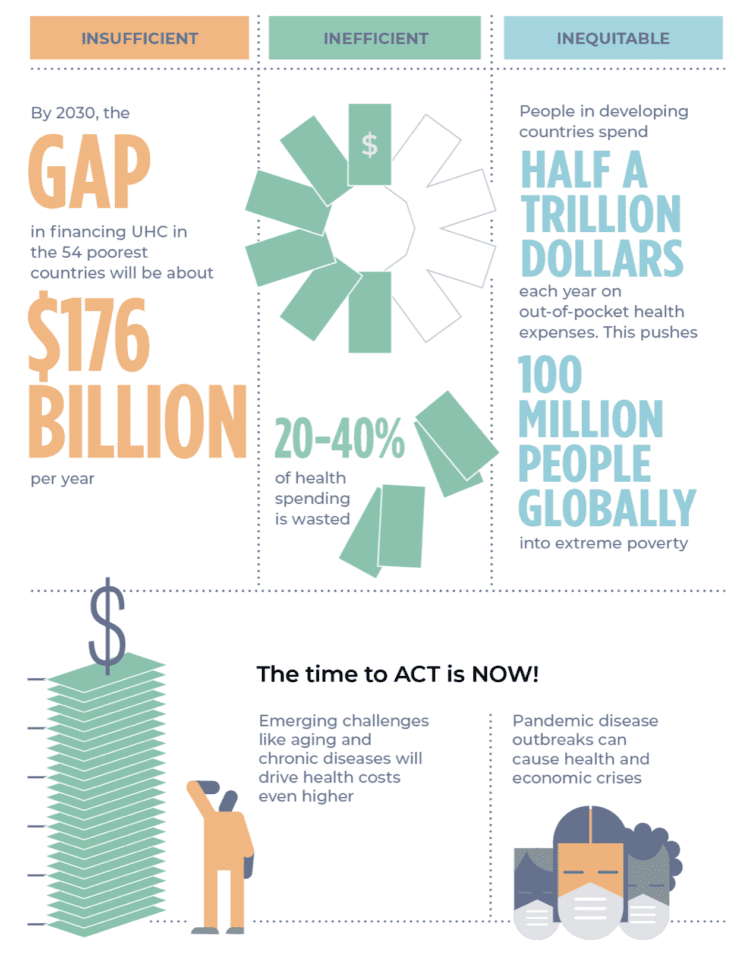

The majority of developing countries will fail to achieve their targets for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the health- and poverty-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) unless they take urgent steps to strengthen their health financing. Just over a decade out from the SDG deadline of 2030, 3.6 billion people do not receive the most essential health services they need, and 100 million are pushed into poverty from paying out-of-pocket for health services. The evidence is strong that progress towards UHC, core to SDG 3, will spur inclusive and sustainable economic growth, yet this will not happen unless countries achieve high-performance health financing, defined here as funding levels that are adequate and sustainable; pooling that is sufficient to spread the financial risks of ill-health; and spending that is efficient and equitable to assure desired levels of health service coverage, quality, and financial protection for all people— with resilience and sustainability.

The UHC financing agenda fits squarely within the core mission of the G20 to promote sustainable, inclusive growth and to mitigate potential risks to the global economy. All countries stand to benefit from realizing quality and efficiency gains and freeing productive resources in one of the largest global industries.

All countries will also benefit from health financing designed to strengthen health security, thus reducing the frequency, spread and impacts of disease outbreaks, and other negative cross-border spillover effects of failing health systems. Anchoring this agenda in the G20 Finance Track and promoting joint leadership by finance and health ministers provides the opportunity to break down the silos and tackle the political economy challenges that continue to hamper progress toward high-performance health financing for UHC.

High-performance health financing advances UHC and sustainable, inclusive growth

It is no longer plausible to argue that health spending is purely consumption. High-performance health financing is an investment that benefits the economy through six main channels:

- Building human capital. Investments in essential primary and community health services such as maternal, neonatal, and child health interventions, including immunization and nutrition, fuels the creation of human capital during children’s critical early years, laying the foundation of improved educational performance and earning potential. Essential promotive, preventive, and curative health services boost workers’ productivity throughout their lifetimes, often with rapid impact.

- Increasing skills and jobs, labor market mobility and formalization of the labor force. The changing nature of work requires skills such as complex problem-solving, teamwork, innovation and self-reliance. Investing in health is a prerequisite to build and maintain these skills and increase countries’ capacities to innovate and generate jobs and growth. High-performance health financing also guarantees financial protection regardless of where people live or their employment status, making it easier for people to change jobs and take advantage of new opportunities. It also reduces the costs for private firms to grow and create jobs, increasing the rate of workforce formalization and the proportion of people in full-time employment.

- Reducing poverty and inequity. Scaling up prepaid and pooled financing to reduce out-of-pocket payments can have a swift, substantial benefit for poverty reduction. Financial protection has other benefits: people no longer need to sell assets or borrow to meet health payments. They conserve resources that they can then spend or invest in other ways. Financial protection also allows the sick and poor to protect, maintain and improve their health and increase their earnings. As a result, income inequality falls.

- Improving efficiency and financial discipline. Improvements in the efficiency of pooling and purchasing allow expanding the range and quality of guaranteed health services and increasing the extent of financial protection within existing resource envelopes, while controlling cost escalation. Combined with measures to increase efficiency in resource mobilization, they ensure financial discipline in the sector over the short and long term. This can have an immediate impact on public spending given that the health sector now represents a significant share of government expenditures in many countries—on average more than 11 percent.

- Fostering consumption and competitiveness. Financial protection frees people from making precautionary savings and can stimulate expenditures on other goods and services. The ability of a country’s entrepreneurs, companies, and workers to continually adapt and innovate is paramount to future competitiveness, facilitated by the impact of UHC and health and human capital accumulation. By driving efficiency gains in the health sector, health financing also frees productive resources for new strategic uses, supporting countries to gain or keep a comparative advantage in international trade.

- Strengthening health security. The West Africa Ebola crisis of 2013-2016 demonstrated that pandemics can leave lasting economic scars and set development back for years, if not decades. Investments in preparedness capabilities including surveillance, primary and community health workers, public-health laboratory networks, and information systems are essential to detect and mitigate infectious disease outbreaks before they spread out of control. In addition to saving lives, investing in preparedness and early action to stop outbreaks also help prevent macro-economic shocks and much more costly emergency response efforts.

Health promotion taxation to help close the UHC funding gap

Excise taxes on health “bads” such as tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages remain underutilized as tools to improve health (Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health 2019; Marquez and Moreno-Dodson 2017). Excise tax increases that raise the prices of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages by 50 percent could raise additional revenues of $20 trillion worldwide over the next 50 years (Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health 2019).

A similar increase in retail prices could generate additional revenues of approximately $24.7 billion in 2030 in the 54 countries that are unlikely to reach UMIC status by 2030. Of the $24.7 billion total revenue gain, approximately $5.9 billion would be generated in LICs and $18.8 billion in LMICs. These excise tax increases would raise the tax-to-GDP ratio on average by 0.7 percentage points in LICs and 0.7 percentage points in LMICs. If the additional revenues were allocated to health according to the current levels of prioritization in government spending, the financing gap for UHC would decrease by $0.5 billion in LICs and $0.8 billion in LMICs. If allocated to health at a level of 50 percent, the excise tax increases would lower the financing gap by $2.9 billion in LICs and $6.6 billion in LMICs. The tax increase would have the additional advantage of reducing future health care costs by curbing the growth of non- communicable disease (NCD) burdens.

Make health financing future-fit

Leverage health-finance tools to mitigate NCD burdens: bolstering sustainability while saving lives. One way of mitigating the adverse impact of the NCDs tsunami has on countries is to ensure adequate funding for health promotion and disease prevention as part of healthy aging policies.

Another important contribution of health financing is to reduce population risks of developing NCDs through health taxes on products that cause them. These taxes reduce consumption of health-damaging products, improve population health and individual productivity, and cut future treatment costs—making health financing more sustainable in the medium term.

They can also substantially boost government revenues (Junquera-Varela et al. 2017; Marquez and Moreno-Dodson 2017; Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health 2019). Importantly, because of their health benefits, these taxes are generally more acceptable to the population than other forms of taxation, though often opposed by powerful interest groups. Examples that have been applied in different countries include taxes on tobacco, alcohol, sugar-sweetened beverages, salt in processed food, and carbon.