Contrary to popular belief, the majority of young people in the United States do not use nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs, and the number of those who use has declined in recent years.

A number of factors contribute to whether a young person will use an addictive substance, the age at which he or she will do so, whether it will take the form of experimentation or occasional use or frequent or intense use, and what the specific consequences will be. Given the variability in the causes, trajectories, and consequences of substance use, preventing it and mitigating its harms can seem overwhelming and daunting.

However, preventive strategies can reduce the likelihood of youth substance use and addiction, especially if they are research-based, comprehensive, age-appropriate, tailored to individual needs, and implemented across the domains of influence over a child’s life, including within families, schools, and communities.

The Partnership to End Addiction has released a new report titled “Rethinking Substance Use Prevention“. The report focuses on the need for an earlier and broader approach for prevention.

Research on substance use and early childhood development shows that how children will grow up is determined by experiences in early and middle childhood, coupled with biological vulnerabilities.

This is why a broader approach to substance use which starts in early childhood and includes not only the child, but also parents, families and communities is a necessity. Such an approach should promote health and resilience beyond risk reduction and address broader social determinants of risk and protection that are essential for achieving significant, equitable, and sustainable outcomes.

The report calls for a broader and earlier approach to protecting youth from substance use and addiction. The report provides a comprehensive, evidence-based case to start prevention early.

By intervening earlier and more broadly, substance use and its negative consequences can be prevented much better.

What is prevention?

Prevention is helping parents have a conversation with their children about drugs. It is counseling for a young person experiencing anxiety, stress, or trauma. It is educating parents about the latest drug trends. It is training physicians to screen young patients for substance use. It is incorporating lessons about addiction science into biology and chemistry classes. It is policies prohibiting the advertising of tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana products. It is peer education and support.

Prevention includes any of these activities.

And effective prevention is also easy access to diapers and affordable child care for new parents so that they can support and actively engage with their babies. It is policies that help to reduce poverty, offer paid family leave, address childhood trauma, and guarantee health insurance coverage for parents’ mental illness and addiction treatment so that children grow up in a healthy and stable family environment. Prevention is engaging and accessible after-school and weekend activities for young people so that they are stimulated and challenged within a safe environment. It is literacy skills, guidance and mentorship from a caring adults, social and emotional learning, and opportunities for civic engagement so that children feel a sense of worth, hope, and belonging.

Traditional school- and community-based prevention programs are and remain necessary but not sufficient to effectively address one of the biggest preventable public health problems: substance use and addiction.

Why prevention matters?

Adolescence is the developmental stage that represents the height of vulnerability for experimentation with and initiation of substance use and for the consequences of such use, including the risk of developing addiction.

The majority of young people in the United States do not use nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs, and the number of those who use has declined in recent years.

Among those who do engage in substance use, some experiment but do not end up using regularly, others stay involved for longer but do not experience significant consequences, and still others end up with a lifetime of sickness and suffering.

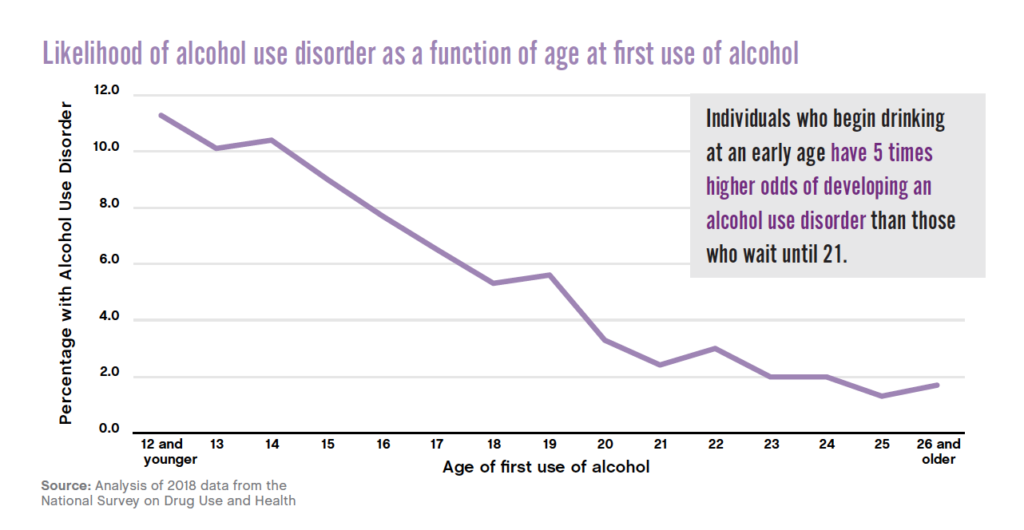

A common theme across addictive substances, however, is that the consequences to the person using them tend to be more intense if use begins at a young age.

The co-occurrence of risk behaviors is common among young people, such that those who engage in one risk behavior tend to engage in multiple risk behaviors. For example, those who report having ridden with a driver under the influence of alcohol (DUI) are nearly 10 times more likely to also report having driven after consuming alcohol themselves. And most youth who report using a given addictive substance say they use more than one.

With regard to substance use specifically, three in 10 high school students in the United States report consuming alcohol in the past month and, by the time they leave high school, nearly half (48.7%) have used marijuana and 17.4% have used other illicit drugs. Even though the prevalence of substance use behavior reflected in these data indicate that most young people do not engage in substance use on a regular basis, the majority of adolescents do report having tried one or more addictive substance in their lifetime. And a notable proportion start early: an estimated 15%, 8%, and 6% of students said they’ve tried alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana, respectively, before age 13.

Youth substance use not only increases the risk of addiction but also has profound health, social, and financial costs.

It is directly linked to the three leading causes of death among adolescents – accidents, homicides, and suicides – and is implicated in poor academic performance, cognitive impairment, school dropout, unsafe sex, unintended pregnancies, mental health problems, violence, criminal involvement, unsafe driving, and numerous potentially fatal medical conditions. The more frequent and intense the use of addictive substances among young people, the greater the consequences. Use of more than one substance only compounds the risk of negative outcomes.

Key policy priorities

There are three sets of recommendations in the report.

- Promote collaboration and coordinate funding and management of youth protective services.

- Increase and align funding for substance use prevention and its early indicators.

- Bolstering the quality and reach of traditional substance use prevention strategies.

- Alleviating structural and environmental factors linked to youth substance use risk.

- Supporting direct services to parents to strengthen effective parenting practices.

- Supporting direct services to children to promote health and reduce risk.

- Prioritizing prevention research that assesses the benefits of an earlier and broader approach. Consider downstream effects of funding cuts to programs and services.

Key practice priorities

The report outlines key practice priorities for parents, for educators, for healthcare providers, and for policy makers.

For parents and other caregivers in the family and community: Through specific skills and practices, parents and other caregivers can support and empower children, promote resilience, and protect their health, safety, and well-being.

Specific actions include the following:

- Start early,

- Know the facts,

- Be a good model for health and resilience,

- Communicate openly and honestly,

- Share expectations,

- Monitor behavior,

- Take a health, not punitive, approach,

- Encourage healthy risk-taking and emotion expression,

- Use positive reinforcement, and

- Know children’s risk level and respond accordingly.

For educators the report calls for adopting an earlier and broader approach to prevention that promotes child health, wellness, and resilience and addresses shared risk factors across a range of health issues. With enough funding, schools can provide effective social-emotional learning, substance use prevention programming, routine screening for risk, and counseling services and other interventions for children who need them. There are also a specific actions given in the report for educators.

Healthcare providers can:

- Work with parents, community organizations, educators, social service agencies, and policymakers to help ensure that prevention messaging and initiatives are based in the evidence.

- Become more involved in the education, training, and support of those working in nonmedical settings to identify and appropriately manage substance-related risk factors in the populations they serve.

- Be involved in promoting and advocating for legislative and regulatory measures that control the availability and accessibility of addictive substances, especially to youth.

There is a list of specific actions for healthcare providers to get involved with prevention as well.

Communities and policy makers focus on population-based approaches to preventing and reducing substance use and its associated problems. They tend to be less concerned with targeting individual risks and more focused on cultural, social, and environmental changes that can promote health within the community. This might include social marketing* and public awareness campaigns, health and wellness promotion, and public policy changes.

Community approaches to prevention also emphasize collective action across community sectors, including strategies aimed at the school and health care environments. Communities can engage in prevention efforts that combine evidence-based programs and policies for increased impact on the population and ensure prevention reaches groups of people in a variety of settings (e.g., schools, media, community-serving organizations) and with varying levels of risk.

Local substance use prevention policies also commonly target the population more broadly by imposing taxes on legal addictive substances, restricting tobacco and alcohol retail outlet density, limiting days and hours of sale of legal substances, raising the minimum legal age of sale or purchase, and instituting prescription drug monitoring programs.

*Social marketing

Social marketing uses successful commercial marketing methods to promote public health or other social goals

Communities’ and policymakers’ prevention efforts have the potential for large scale influence on substance use behaviors. Unfortunately, these efforts and policies are rarely implemented widely or enforced adequately, tend to change over time, and are subject to resource limitations, political will, and competing interests.

Key research priorities

Measuring and tracking changes of key risk factors for youth substance use helps to establish an evidence base that can expand prevention interventions beyond the conventional approach such as interventions that reduce financial stress on families and support child and parental mental health.

Research can demonstrate that intervening earlier and more broadly can better prevent substance use in adolescence and put children on a healthy path to adulthood. This can ultimately steer more youth and adults away from developing addiction.

There is also a list of specific actions for researchers to promote healthy child development and prevent substance use.

Encouraging trends

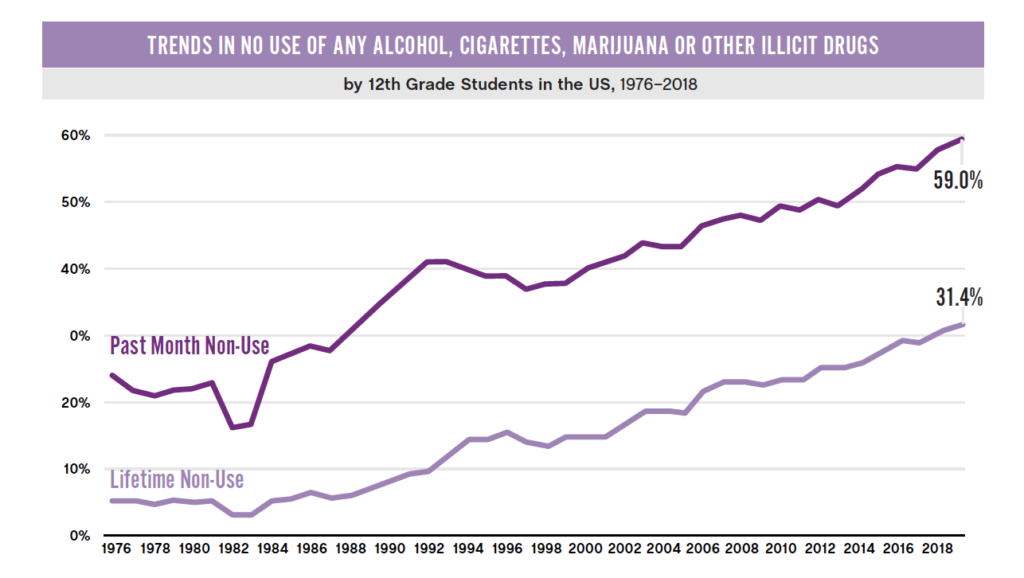

Although the use of certain substances, specifically nicotine and marijuana, among youth has been increasing in recent years, other trends that have emerged over the past few decades are encouraging: use of cigarettes, alcohol, and certain other addictive substances has been declining among adolescents and young adults, the average age of first use of any addictive substance has been increasing, and more and more young people are choosing to abstain completely from substance use.

This is an encouraging pattern with significance for young people themselves, communities and society overall. But the reasons behind a nationwide shift in the prevalence of this sort of complex behavior are multifaceted. It is possible that the decline is due, at least in part, to the advancement of evidence-based prevention interventions and programs. Notably, however, as rates of adolescent substance use have fallen, fewer young people have reported receiving or being exposed to prevention messaging or education, suggesting that prevention programming alone is likely not responsible for the downward trend.

| INCREASING TRENDS | DECREASING TRENDS |

| Age at first substance use | Maternal postpartum depressive symptoms |

| Positive attitudes toward school | Corporal punishment (i.e., harsh discipline) |

| Parental monitoring | Conduct problems |

| Strong parental disapproval of substance use | Youth engagement in sex |

| Strong youth disapproval of peer substance use | Time spent without parental supervision |

| Parental affirmation | |

| Youth participation in extracurricular activities | |

| Youth wearing a car seatbelt | |

| Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) programs |

Examining changes in the factors that increase or decrease the risk of youth substance use might point to something larger than prevention programming as an explanation. For example, research shows that engagement in other risky behaviors, such as fighting and sexual activity with multiple partners, has also been decreasing. These tandem downward trends appear to be related not to targeted prevention efforts for distinct behaviors but rather to changes in a broader phenomenon that contributes to multiple risky behaviors. A number of factors that are known to be protective against youth substance use – including positive attitudes toward school, parental monitoring, engagement in extracurricular activities, and social-emotional learning – have trended upward. At the same time, on the decline are several factors associated with heightened risk for substance use, including maternal postpartum depression, corporal punishment, and conduct problems.

Taken together, these shifts in a generally positive direction might represent the culmination of the past few decades of public health and educational advances focused on improving youth well-being through greater attention to early childhood development and growing appreciation for the role social-emotional health plays in fostering resilient youth.

Download the complete report

Access the full report here.