The latest government data show that the amount of people consuming alcohol is declining in India. A steady trend of decline is seen from 2005 to the latest National Family Health Survey (2019-21) data. However, this data does not align with sales data and WHO data which show an increase in sales and consumption of alcohol products in India.

The main explanation for the discrepancy is that heavier alcohol users are consuming more alcohol now.

The National Family Health Survey 5 (NFHS-5) was conducted between 2019 and 2021. The survey found that among the Indian population between the age of 15 to 54 years, 22.9% of men and 0.7% of women consumed alcohol. This is a decline in alcohol consumption from the previous NFHS-4 in 2015-16 from 29% for men. For women, the alcohol consumption rate has remained the same as in NFHS-4.

In previous years as well NFHS recorded declines in Indian alcohol consumption. Between NFHS-3 (2005-06) and NFHS-4 (2015-16), the number of Indian men who consumed alcohol declined from 32% to 29%. In the case of women, this number declined from 2.2% to 1.2%.

The state with the highest decline in alcohol use among men aged 15 to 49 years was Tripura where alcohol use fell from 57.6% in 2015-16 to 35.9% in 2019-21. This is still above the national average of 22.9%. Apart from Tripura, alcohol consumption among men declined by over 10% in at least seven states/ Union territories: Mizoram, Chhattisgarh, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Chandigarh, Bihar, and Kerala. Comparatively, Goa, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Delhi and Jharkhand reported an increase in alcohol use.

Discrepancy in the data

The NFHS data does not add up with other alcohol sales and consumption findings in the country. The Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) reported that India’s alcohol industry was worth $52.5 billion and was estimated to grow by 6.8% year-on-year till 2023.

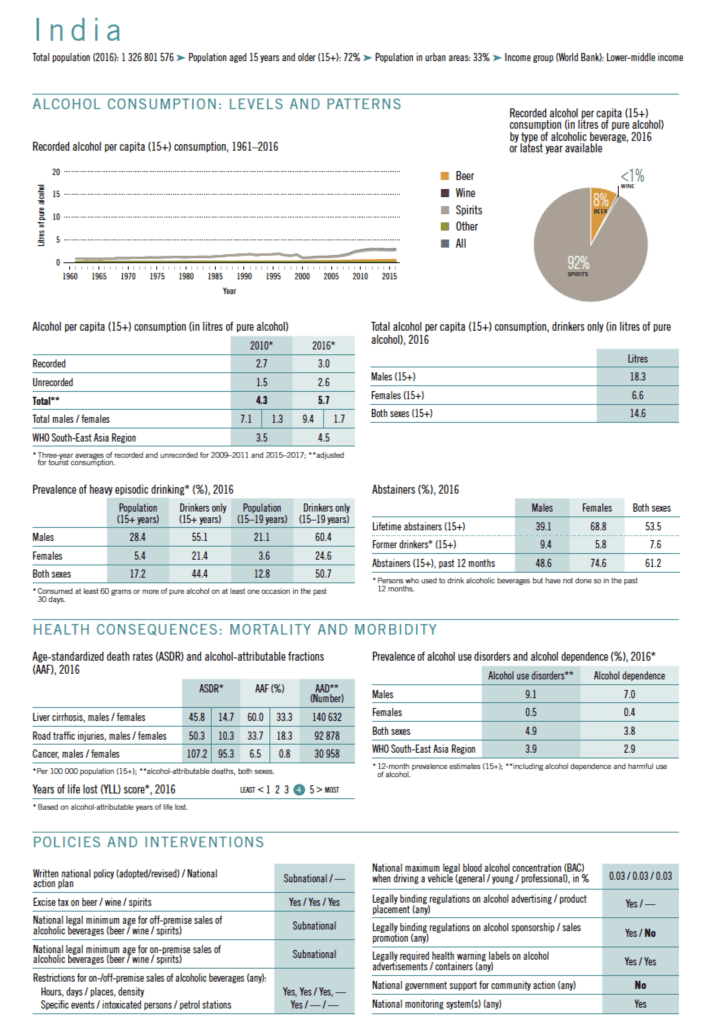

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2018 Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, estimated during 2010 to 2017, there was a 38% increase in per-capita alcohol consumption among individuals aged 15 years or older in India.

The survey (NFHS-5) was conducted between 2019 and 2021, which can be considered abnormal years. Hence, wide variations in household interviews are expected,” said Monika Arora, director of the health promotion division at the Gurugram-based think tank Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), as per The Print.

During this time period, we witnessed two significant lockdowns and as a result, the access to alcohol became restricted.”

Monika Arora, director, health promotion, Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI)

Ms. Arora who is also the leader of HRIDAY, a member organization of Movendi International, says that the NFHS-5 data cannot be compared with the NFHS-4 data due to COVID-19 and lockdowns during the NFHS-5 data collection period.

If there was a fall in liquor consumers in India, that should reflect in the sales, revenue and other market data, but that’s not visible here,” added Monika Arora, director of the health promotion division at Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), as per The Print.

In fact, the beer and spirits sales data in India has shown a sharp increase in 2021, and companies even reported higher volumes compared to pre-COVID sales.”

Monika Arora, director of the health promotion division, Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI)

According to Ms. Arora and PHFI there could be several reasons for the mismatch between NFHS alcohol data and alcohol sales data.

- Respondents may have not answered truthfully if the data collection was during a lockdown since alcohol sales were restricted during this time and they may have had illicit alcohol.

- Data could have been collected at a time when participants had a temporary behavior change due to access restrictions and multiple health authorities issuing advisories to stay healthy to avoid severe COVID-19 outcomes during the lockdown.

Pal Singh Balhara, additional professor of psychiatry at the National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre (NDDTC), AIIMS-Delhi says that NFHS data showing declining alcohol consumption while alcohol sales increased is due to a smaller proportion of those who use alcohol using it much more heavily than before.

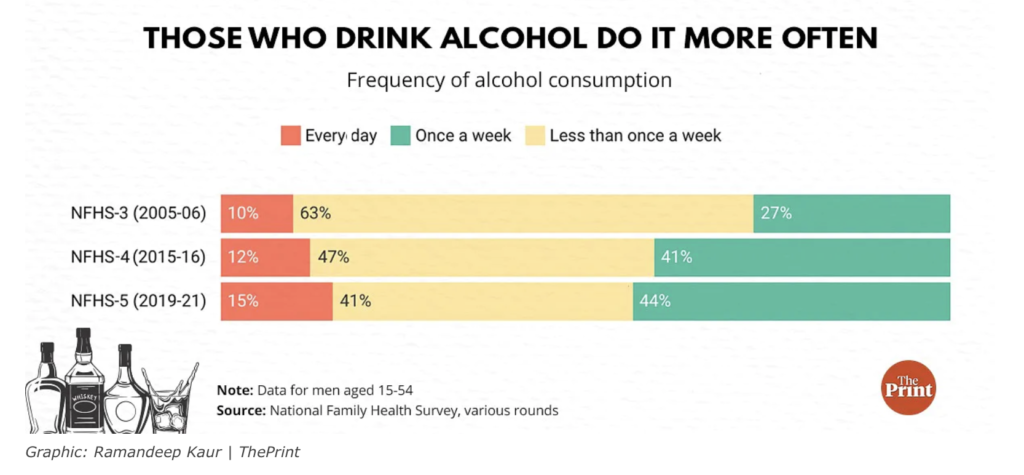

NFHS-5 data back this claim up since it shows that while the number of Indians who consume alcohol has declined, there has been a significant increase in the frequency of alcohol consumption among those who consume.

- In NFHS-3 conducted between 2005 and 2006, only 10% of the respondents were daily alcohol users. By 2015-2016 this figure grew to 12% and according to the latest data from 2019-2021 there are 15% daily alcohol users.

- Those consuming alcohol once a week has also increased.

- In 2005-2006, 27% of the respondents were consuming alcohol once a week. By 2015-2016 this figure increased to 41% and by 2019-2021 it further rose to 47%.

- Along with the increased frequency of daily and once-a-week alcohol use, less than once-a-week alcohol use has dropped from 63% in 2005-2006 to 41% in 2019-2021.

Alcohol harm and policy in India

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2016, in India alcohol caused,

- 140,632 deaths due to liver cirrhosis,

- 92,878 deaths due to road traffic injuries, and

- 30,958 deaths due to cancer.

India is a country that is placed on the higher end for years of life lost due to alcohol.

Despite the heavy alcohol burden, the alcohol policy in India remains subnational. This has led to various different alcohol laws across states.

Big Alcohol lobbying and policy interference in India

Big Alcohol has been hammering away at Indian alcohol policies for years.

As Movendi International has reported previously, Pernod Ricard has been lobbying against import taxes on foreign liquor in India for years.

India’s current import tax not only generates more revenue for the Indian government but also protects Indian society from being saturated with imported alcohol products and further accelerating alcohol harm in Indian communities.

According to Thibault Cuny, Pernod Ricard, South Asia CEO, the company doesn’t want to just reduce the import taxes in India. They want the taxes completely scrapped, so the alcohol giant can flood India with their products, drive higher consumption, and maximize profits.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Big Alcohol unleashed a well-planned lobby campaign pressuring state governments to legalize home delivery of alcohol. This has been a systematic campaign that led some states to trial various online sales methods, including a token system. However, the lockdowns halted some of these trials.

Another example of Big Alcohol’s exploitative business practices to increase alcohol sales and consumption for even more profit is Diageo’s market strategy in India.

Movendi International previously reported how Diageo plans to dominate the Indian market. The main aspects of Diageo’s strategy to intervene in public health policy and eliminate threats to sales and profits are:

- Engaging in road safety programs;

- Advocating for the weakening of local alcohol policies under the guise of increasing Indian States’ ease of doing business rankings; and

- Intervening and influencing tax policies.

Diageo’s strategy has led to policies that benefit the alcohol industry at the cost of the health and well-being of Indian people and communities. For example, ISWAI – the lobby group Diageo is funding – has been running programs to “co-create” “mutually beneficial” tax policy for imported brands with excise officials. In 2018 this led to a 30% price cut for Johnnie Walker Black Label in Karnataka.

Meanwhile, according to independent research current levels of alcohol taxation in India are by far too low to help cover the costs of alcohol harm.