Heineken’s land grab and what it means for the local people

An Ethiopian farming village was razed to the ground to make way for a new Heineken brewery. Five farmers tell their story, reported by investigative journalist Olivier van Beemen in Follow The Money.

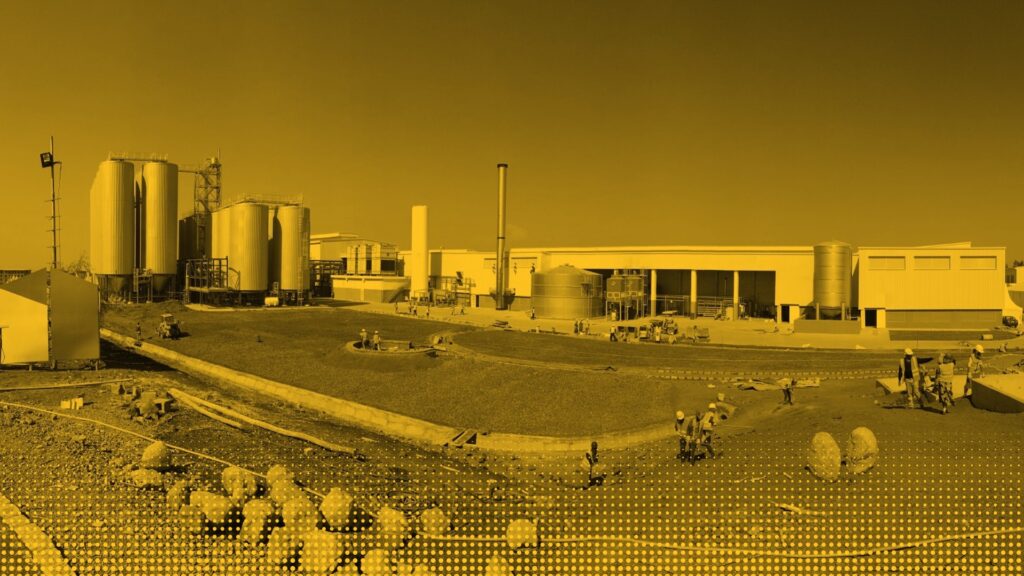

It will soon be ten years ago that Heineken started construction work on a new brewery on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Lilianne Ploumen, the then Dutch Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, laid the first stone during a festive ceremony.

But what looked nice from a Dutch politician’s and beer giant’s perspective was a life-altering and even a life-shattering experience for local people. For the first time, Ethiopians who lived on the site of the current Heineken beer factory tell about their forced departure, as per The Continent.

This case, exposed by Mr van Beemen, sheds light on the importance of the “International Corporate Social Responsibility (ICSR) law” that is currently being drafted in the Netherlands. This law is intended to prevent companies from looking the other and ignore alleged crimes such as those that took place during the construction of Heineken’s brewery in Ethiopia.

In February 2013, Kilinto was a small village on the outskirts of Addis Ababa. The people living there were promised to benefit from the Dutch beer giant’s new factory.

Everyone benefits from this,” said Lilianne Ploumen, the then Dutch Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, as per The Continent.

Lilianne Ploumen, former Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, the Netherlands

But ten years later, the people in a working-class area with unpaved roads just a few minutes’ drive from Heineken’s facility say the former minister’s promises never mateiralized. About 200 villagers were evicted from their land to make way for the new brewery, and some of them were resettled here.

While the farmers did receive some compensation in the form of a small plot of land and a one-off cash payment, they consider this to be far below the value of the land that was taken from them.

It was a depressing time,” says Tolosa Balacha, 69, according to Olivier van Beemen reporting.

The plot was too small to build a new house and the money too little to buy one. Now I’m a security guard on a construction site. My life is standing still.”

Tolosa Balacha, local resident

On a piece of land of 1,000m2, he grew barley and teff, Ethiopia’s staple food, before he was made to move against his will. In compensation, he received a piece of land measuring 50m2 plus 60,000 birr – worth just over $2,000 at the time.

Many people had traumatic experiences when the bulldozers and an elite police squad arrived to remove the local people in favor of the Dutch beer giant. And for many people their livelihoods were affected negatively.

Some people were given just 24 hours to leave their home, along with their pets, cows and sheep. And when they refused, they were accused of inciting revolt. In police custody, people from Kilito say they were tortured. They eventually moved and some of them now work at the Heineken factory. For example, one local resident checks and fixes wooden pallets for Heineken, making $40 in a good month, $10 in a bad one, according to Mr van Beemen’s reporting.

It’s humiliating to work there. Stealing our land has made us hate Heineken, but we’re even angrier at the government. They evicted us and gave our land away.”

Anbassa Tesfaye, name has been changed to protect the identity of the local resident

Moral low ground

By law, all land in Ethiopia belongs to the state. Foreign companies that want to build factories or operate farms must rent land from the government – and it is the government that is responsible for relocating and compensating anyone who already lives there.

In recent years, the Ethiopian government has been enthusiastically renting large swathes of its territory to both local and foreign investors, regardless of who is already living there.

Since 2008, some 7-million hectares have been leased to investors.

The land grabs are done mostly without prior consultation and without adequate compensation, sometimes with no compensation, to the evicted farmers and community members,” wrote Samrawit Getaneh Damtew, a legal researcher at the African Union, in a 2019 article in the African Human Rights Law Journal.

Samrawit Getaneh Damtew, legal researcher, African Union

These land grabs across Africa can be understood as a “neo- colonialist scramble for Africa”, of which Ethiopia – as a favourite destination for foreign investors – is the epicentre, according the Ms Damtew. All too often, these land grabs infringe on the rights of the people who were already there.

Heineken for example does not seem to have taken any action to mitigate the risks.

The question of what responsibility a foreign company may have in situations like this has come up in other contexts. In Uganda in 2001, a group of farmers were violently evicted from their land by Ugandan soldiers, to make way for a new coffee plantation owned by the Neumann Group, a German company that is the world’s leading supplier of raw coffee.

The farmers sued the Neumann Group for damages, and the high court issued a damning assessment of the group, saying it had a duty to ensure people on the land were adequately compensated and resettled. Instead they were quiet spectators and watched as cruel, violent and degrading eviction took place through, reports Mr van Beemen.

For Heineken – market domination, for the local people – loss of agriculture and sustainable development

The venture has been a commercial success for Heineken, currently competing with French beer giant Castel to be the dominant beer maker in Ethiopia.

But for the local people the arrival of the Dutch multinational corporation has not led to increased employment. On the contrary: When Heineken entered the Ethiopian market in 2011 by acquiring two state-owned breweries, nearly 1,700 people worked there. Today, Heineken employs just over 1,000 permanent staff, despite building its third brewery at Kilinto.

Heineken’s land in Ethiopia to produce more beer is also the story of a multinational giant from a Western country, supported by the political leadership of that country, negatively affecting several dimensions of sustainable development in a developing country. The beer giant’s move to push out people from their land and livelihoods illustrates how the alcohol industry negatively affects food production and food security, poverty eradication efforts, biodiversity, and social and human capital.

The stories of local residents that Mr van Beemen reported illustrate the conflict of interest between achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as “Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss” (SDG 15, Life on Land) on the one hand and alcohol companies pushing for rising alcohol use, sales, and profits.

The report on the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World showed that as many as 828 million people experienced hunger in 2021, representing a rise of approximately 150 million in food-insecure people since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Extreme poverty remains at pre-pandemic levels.

Biodiversity is being lost at alarming rates. The second edition of the Global Land Outlook shows that up to 40% of all ice-free land is already degraded, and stresses that the need to build social and human capital to restore natural capital.

Heineken’s Kilinto beer factor, built on the land of people who produced food and made a decent living, is a symbol for failing development efforts.

The transition to achieve food security for all, to eradicate poverty and to protect and restore land and ecosystems on which all life on earth depends is failing because multinational corporations, such as Heineken, are putting their profits before any sustainable development considerations.

In 2012, the Committee on World Food Security unanimously endorsed the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Forest and Fisheries (VGGT). The VGGT were developed in response to land grabs around the world that contributed to the 2008 food crisis.

The overarching reason for implementing the VGGT is to “achieve food security for all and to support the progressive realization of the right to adequate food.”

Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) adopted a landmark decision on land tenure in 2019. This decision was reaffirmed at the 15th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 15) in May 2022. It recognizes that “who owns land, who has rights to use land and natural resources and how secure these rights are significantly influences the way that land is managed.”

These two decisions represent a major step forward in advancing rights-based approaches to achieve SDG target 15.3 on land degradation neutrality (LDN), as well as targets on poverty reduction, food security, and gender equality.

Decisions like those need to be protected from the unethical practices of alcohol companies like Heineken in order to advance global justice and achieve development for all.