Alcohol consumption as a socially contagious phenomenon in the Framingham Heart Study social network

Research article

Abstract

The researchers use longitudinal social network data from the Framingham Heart Study to examine the extent to which alcohol consumption is influenced by the network structure.

The researchers assess the spread of alcohol use in a three-state SIS-type model, classifying individuals as abstainers, moderate alcohol users, and heavy alcohol users.

The study finds that the use of three-states improves on the more canonical two-state classification, as the data show that all three states are highly stable and have different social dynamics.

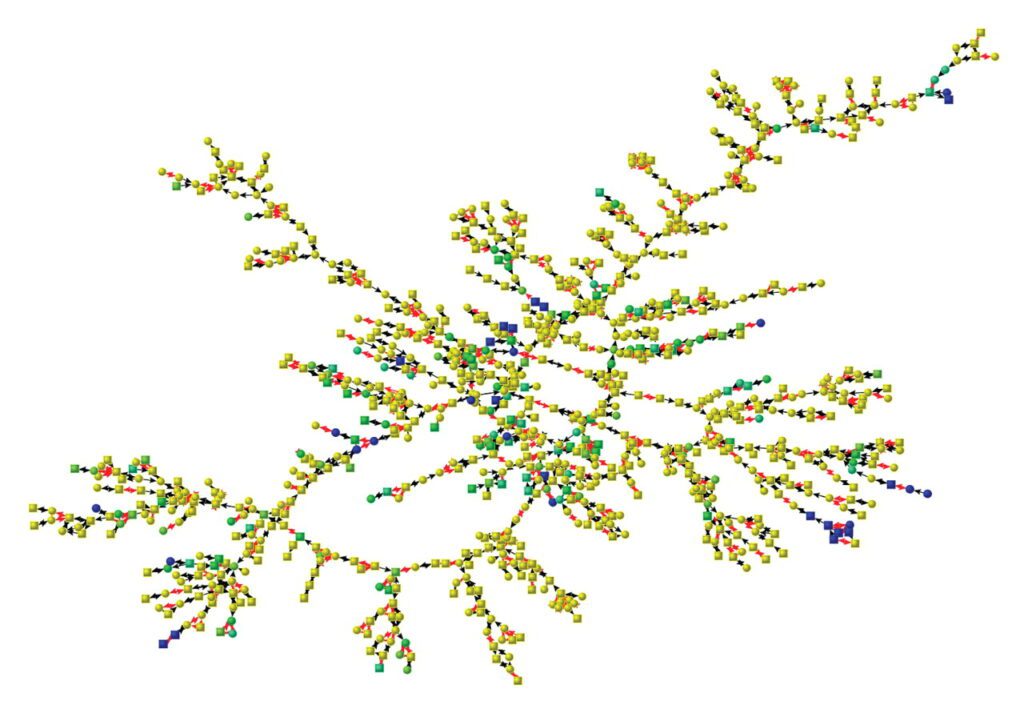

The researchers show that when modelling the spread of alcohol use, it is important to model the topology of social interactions by incorporating the network structure. The population is not homogeneously mixed, and clustering is high with abstainers and heavy alcohol users.

The study finds that both abstainers and heavy alcohol users have a strong influence on their social environment; for every heavy alcohol user and abstainer connection, the probability of a moderate alcohol user adopting their alcohol consumption behaviour increases by 40% and 18%, respectively.

About the Framingham Heart Study

The Framingham Heart Study is a long-term, ongoing cardiovascularcohort study of residents of the city of Framingham, Massachusetts. The study began in 1948 with 5,209 adult subjects from Framingham, and is now on its third generation of participants. Prior to the study almost nothing was known about the epidemiology of hypertensive or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Much of the now-common knowledge concerning heart disease, such as the effects of diet, exercise, and common medications such as aspirin, is based on this longitudinal study. It is a project of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, in collaboration with (since 1971) Boston University. Various health professionals from the hospitals and universities of Greater Bostonstaff the project.

The researchers also find that abstinent connections have a significant positive effect on heavy alcohol users quitting alcohol consumption.

Using simulations, the researchers find that while both are effective, increasing the influence of abstainers appears to be the more effective intervention compared to reducing the influence of heavy alcohol users.

Introduction

Alcohol dependence is the result of a complex interaction between many factors:

- social factors, from general life satisfaction to availability of the substance;

- psychological factors, such as choice processes and craving; and

- genetic vulnerabilities.

Although extensive research has focused on the impact of the social environment on alcohol dependence, the underlying interactions are still recognized as complex and multifaceted. Initial use is affected by parental influence and exposure to peers who use drugs.

While there are many psychological theories and formal models of alcohol use, the impact of the social environment is often ignored. At the same time, social approaches often forgo the exact structure of the social environment as the exact process of contagion of alcohol use is not well understood.

However, in recent studies, the significance of network structure in contagion processes has increasingly been acknowledged. In the context of alcohol use, the importance of accounting for population heterogeneity has been demonstrated.

In this study, the researchers leverage longitudinal social network data from the Framingham Heart Study to explore the influence of the structure of the social environment on alcohol consumption patterns.

The influence of social connections on behaviours such as alcohol consumption, eating habits, depression, sleep patterns and smoking has been compared to the spread of infectious diseases.

The concept of ‘social contagion’ captures this phenomenon and suggests that mathematical models commonly used in epidemiology may be well suited to unravelling the dynamics of the spread of such behaviours. While numerous studies have investigated the social transmission of different behaviours, the application of epidemiological frameworks to noncommunicable diseases is still in its infancy.

The binary classification of individuals as alcohol users or non-alcohol users may not accurately reflect the spectrum of alcohol use observed. To address this, a three-tiered classification system – abstainers, moderate alcohol users and heavy alcohol users – has been proposed.

The current study aims to assess the implications of this nuanced categorisation and its effectiveness in providing a more intricate understanding of alcohol use patterns. The researchers also assess the consistency of the observed data with the assumptions of their epidemiological model and identify significant parameters that inform the study about the mechanisms behind the transmission of alcohol use behaviour. Finally, they aim to dissect the complexity of the spread of alcohol consumption by analysing the role of different alcohol consumption categories.

Understanding the extent of social influence exerted by each category and their respective vulnerabilities is crucial. In addition, simulation experiments designed to test potential public health interventions will allow to assess the effectiveness of different strategies aimed at mitigating the spread of alcohol use.

Background

Social contagion of alcohol use

Although alcohol consumption has been shown to behave like a ‘socially contagious’ behaviour, it differs from infectious diseases and other behaviours in a number of ways that affect the precise modelling approach.

- First, one should apply an SIS-type model rather than an SIR-type model, as it is impossible to become immune when dealing with behaviour.

- Secondly, it has been shown that there is a large, stable, common moderate alcohol consumption state in which 98% of years of recreational use are followed by another year of moderate alcohol use.

- This moderate alcohol intake consists of an average weekly consumption of one to seven alcoholic drinks for women and one to fourteen alcoholic drinks for men. When trying to understand longitudinal patterns, it may therefore be important to distinguish moderate or recreational alcohol use from heavy alcohol consumption, which is associated with mental and biophysical health risks.

- The study shows that it is important to distinguish between abstainers, moderate alcohol users and heavy alcohol users, not only in terms of biophysiological consequences, but also to capture the dynamics of their spread across a population.

- Finally, while infectious diseases can generally only be transmitted through physical contact with an infected person, behaviour can also be adopted through a variety of other factors. Examples include cultural changes such as changes in normality, differences in availability, advertising that promotes or discourages alcohol use, and the effects of policy interventions. This non-social or ‘spontaneous’ or ‘automatic’ transition must therefore be taken into account. This applies not only to increases in alcohol use, but also to reductions and cessation.

Within the field of epidemiology, there is growing evidence that the properties of real-world social topology resulting from the heterogeneous connectivity patterns have an irrefutable impact on the behaviour of epidemic spread.

Behaviours that spread socially do so slowly, mostly through individuals with whom one has social ties and spends a lot of time. As there is great heterogeneity in these social ties, describing the social environment of individuals becomes even more important for representing the interpersonal spread of behaviour.

A basic implementation of social structure in SIR-type models is to increase the number of compartments, for example by grouping into different age or risk groups, or by compartmentalising spatially. Similar approaches have been applied to noncommunicable diseases. For example, in the modelling of university binge alcohol use by Manthey et al. (2008), where individuals from each starting year are separated into different spatial compartments. Homogeneous mixing still occurs within individuals from these years, but mixing, and hence contagion, between individuals from different years is reduced. However, a more accurate representation of social structure is provided by social networks, where each individual (node) has connections (edges) to other individuals with whom they have a social relationship. Constraining the model to a social network thus implies that an infected individual can only spread their behaviour to others with whom they are socially connected.

How networks spread a contagion

- Network connectivity plays a critical role in disease transmission; a highly connected network facilitates rapid spread, while a sparsely connected network can significantly slow disease transmission.

- The degree of clustering is also relevant; if the network consists of poorly connected clusters, it may take a longer time for the disease to spread from one cluster to another, resulting in slower disease progression than in a well-mixed population.

- Heterogeneity in the connectivity of individuals can also lead to super-spreaders; well-connected people who become infected can significantly increase the spread.

- Also influential is the measure of how well the network is mixed; in assortative mixed networks, individuals of a certain type are more likely to be connected to similar individuals. The likelihood that individuals with similar characteristics or behaviours are more likely to be connected to each other than to those who are dissimilar is called spatial correlation.

- For example, spatial correlation is high when heavy alcohol users are more likely to be connected to other heavy alcohol users than would be expected if the network were randomly mixed. As a result, spatial correlation can affect the spread of behaviours or traits within a network, as individuals may be influenced by their social connections to adopt similar behaviours or traits.

Key findings

- The extremes of abstinence and heavy alcohol use are the most influential: moderate alcohol use only influences abstainers to start consuming alcohol, while moderate alcohol users are significantly influenced by both abstainers and heavy alcohol users.

- Heavy alcohol users are influenced only by abstainers, who have a significant positive effect on quitting. However, their transition to moderate alcohol use is not influenced by the number of moderate alcohol users or abstainers.

- Abstainers are significantly more likely to start moderate alcohol consumption if they have more heavy alcohol using contacts.

- There is a strong protective effect for extremes: abstainers are more likely to remain abstainers if they have many abstaining relatives. A similar effect is found for heavy alcohol consumption.

Detailed study results

The researchers analysed alcohol use and network data from the Framingham Heart Study and found evidence of social spread of alcohol consumption among connected individuals. Using this data, the researchers developed an epidemiological model that incorporates three distinct and stable states of alcohol consumption: abstinence, moderate alcohol use and heavy alcohol use. It captures the interplay between spontaneous and socially driven alcohol intake behaviours, yielding transmission rates that quantify the impact of social contagion.

When examining the network structure, the study finds that heavy alcohol users and abstainers are significantly more likely to be connected to others with similar alcohol consumption habits. Specifically, heavy alcohol users and abstainers are 43% and 54% more likely to be associated with similar alcohol consumption individuals.

This highlights the importance of incorporating network modelling into studies of alcohol use behaviour, as epidemiological models that assume homogeneity in populations do not accurately capture the complexities of such behaviours.

A three-state categorisation gives rise to states that are all stable, each with distinct infection dynamics, and that the biophysiological threshold of 7 or 14 alcoholic drinks per week for women and men corresponds well with the stability of these classifications in our data. This threshold can therefore also be considered appropriate for behavioural dynamics.

Which behavior sets the norm and expectations?

Both abstainers and heavy alcohol users have a significant impact on the alcohol consumption habits of their social connections. This influence remained consistent over the 30-year data period.

Each abstaining connection increased the probability of a moderate alcohol user to also abstain by 18%, while each heavy alcohol user increased probability to become heavy alcohol user by 40%.

Abstainers had a significant positive influence on heavy alcohol users to quit alcohol consumption. Conversely, for each heavy alcohol consuming connection of an abstainer, the probability to start alcohol consumption and become a moderate alcohol user is significantly increased.

While moderate alcohol users were found to have a small but significant impact on encouraging abstainers to start consuming alcohol, they had no significant effect on helping heavy alcohol users reduce their alcohol consumption.

Conclusions

Social-alcohol use plays a significant role in “non-problematic alcohol use” and that abstainers too are not immune to peer pressure. Moreover, increasing alcohol use to the level of heavy alcohol consumption is largely influenced by the social environment, but reducing alcohol intake is not, as the spontaneous rate of reduction in alcohol use occurs for 7.5% of the population each year, regardless of the number of moderate alcohol using connections. Although transitioning to total abstinence occurs in only 1.8% of the heavy alcohol consuming population, being surrounded by abstainers increases the likelihood of achieving total abstinence by almost 50% per connection.

Future prevalence of abstinence, moderate and heavy alcohol consumption

Using this calibrated model, the researchers simulated the future prevalence of abstinence, moderate alcohol use and heavy alcohol use. They find that heavy alcohol use will continue to decrease to around 13%, down from 22% in 1975, and abstainers increase to a value very similar to moderate use, of 43%.

Increasing the social impact of abstainers is more efficient than decreasing the social effect of heavy alcohol consuming individuals.

Strengths and limitations

The Framingham Heart Study dataset is unique in that it combines a longitudinal social network with alcohol consumption data over a long period of time. In addition, all participants lived in the same city, which means that many social connections are individuals who are also included in the study. However, as obtaining a social network was not an aim of the study, many social connections were recorded indirectly. Therefore, it is not always clear whether the connections obtained from the unnamed data are people with whom the participant is actually in contact. This could lead to inaccuracies in the social network compared to reality. In addition, the researchers apply an undirected network; however, there could be differences in influence depending on the directionality of the connections: parents will be more influential on their children than the other way around. Another limitation of the dataset is its demographic composition, as it consists mainly of older subjects. As a result, the behaviours and interactions the researchers observed reflect this older cohort and may not be representative of the patterns exhibited by younger adults or adolescents.

In addition, this epidemiological model assumes a linear relationship between the probability of spreading and the number of connections; while this holds for the study’s data with a limited degree distribution, larger data may reveal a more complex relationship. Furthermore, the study’s model does not take into account the non-Markovian elements of alcohol consumption behaviour. Recovered former heavy alcohol users have a significantly higher risk of returning to their previous behaviour in the long term than those who have never had alcohol use disorder. This poses a challenge in measuring transition rates from abstinence to moderate or heavy alcohol use, as these rates may differ between individuals at different stages of alcohol consumption behaviour. Additionally, a significant fraction of heavy alcohol users never attempt to recover and continue to consume alcohol heavily for years. Conversely, another group may be actively trying to recover with varying degrees of success, leading to different recovery rates within the heavy alcohol consuming population.

Although challenging, future work on this topic should therefore attempt to capture the complex and catastrophic nature of alcohol use disorder and addiction. Models integrating psychologically based theories of alcohol use and its impact on the social environment would be able to incorporate non-Markovian dynamics and differentiate between individuals based on their history.