Impact of Introducing a Minimum Alcohol Tax Share in Retail Prices on Alcohol-Attributable Mortality in the WHO European Region: A Modelling Study

Summary

Background

Alcohol use and its burden constitute one of the largest public health challenges in the WHO European Region. Raising alcohol taxes is a cost-effective “best buy” measure to reduce alcohol consumption, but its implementation remains uneven.

This paper provides an overview of existing tax structures in 50 countries and subregions of the European Region, estimates their proportions of tax on retail prices of beer, wine, and spirits, and quantifies the number of deaths that could be averted annually if these tax shares were raised to a minimum level.

Methods

Review of databases and statistical reports on taxes and mean retail prices of alcohol beverages in the Region. Affordability was calculated based on alcohol prices, adjusted for differences in purchasing power.

Consumption changes and averted mortality were modeled assuming two scenarios.

- In Scenario 1, a minimum excise tax share level of 25% of the beverage-specific retail price was assumed for all countries.

- In Scenario 2, in addition to a minimum excise tax share level of 15%, it was assumed that per unit of ethanol minimal retail prices were the same irrespective of alcoholic beverages (equalization).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for different price elasticities.

Findings

Alcohol is very affordable in the Region and alcohol taxes have been under-utilized as a public health measure, constituting on average only 5.7%, 14.0%, and 31.3% of the retail prices of wine, beer, and spirits, respectively.

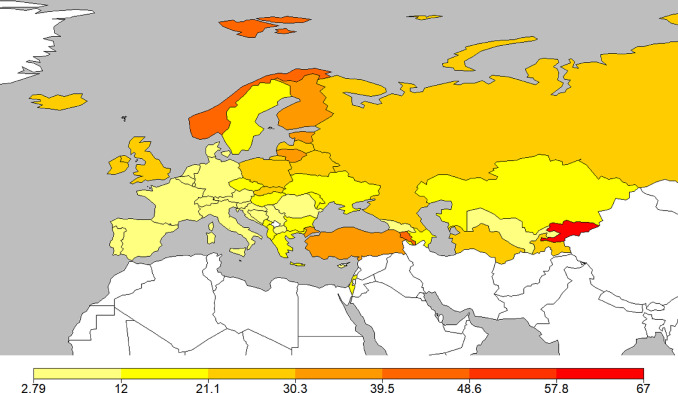

Tax shares were higher in the eastern part of the Region compared to the EU, where various countries did not have excise taxes on wine.

Annually, the introduction of a minimum tax share of 25% (Scenario 1) could avert 40,033 deaths in the WHO European Region (with 753,454,300 inhabitants older than 15 years of age).

If a 15% tax share with equalisation were implemented (Scenario 2), 132,906 deaths could be averted.

All sensitivity analyses with different elasticities yielded outcomes close to those of the main analyses.

Interpretation

Similar to tobacco taxes, increasing alcohol taxes should be considered to be a health-based measure aimed at saving lives. Many countries have hesitated to apply higher taxes to alcohol, but the present results show a clear health benefit as a result of implementing a minimum tax share.

Research in context panel

Alcohol use has been identified as one of the most important risk factors for burden of disease and injury in all comparative risk assessments to date.

The WHO European Region has the highest alcohol consumption level of all WHO Regions, and reduction of the alcohol burden is one of its priorities. To prevent and reduce alcohol harm, the World Health Organization has recommended a number of alcohol policy solutions. Three of are the so-called “best buys” with exceptional cost-effectiveness and impact:

- restricting alcohol availability,

- increasing the price of alcoholic beverages, and

- banning advertising.

The researchers focus the discussion on the control policies related to alcohol taxation, as this “best buy” has been shown to be the most cost-effective both in low- and middle-income and high-income countries.

Evidence before this study and study findings

Alcohol taxation has been identified as one of the “best buys” of alcohol control policy by the World Health Organization. Despite demonstrated effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, reviews demonstrate that governments’ attitudes towards alcohol taxation remain mixed, leaving significant scope for a wider use of policies that would reduce the affordability of alcohol, and alcohol-related harm, in the WHO European Region.

Overall, the proportion of tax in the final consumer prices varied across countries, with countries in the northern and eastern part of the Region having generally higher tax shares included in their final retail prices of alcoholic beverages. The median (mean) tax shares of alcohol prices for beer, wine, and spirits for the WHO European Region were 10.8% (14.0%), 0.8% (5.7%), and 30.6% (31.3%), respectively.

These are very low, especially for wine, with 22 out of all the countries having no alcohol excise taxes at all, and the majority of them located in the EU.

The following countries showed the highest affordability for alcohol:

- Luxembourg,

- Germany,

- Czech Republic,

- Slovakia, and

- Austria.

The countries with the least affordability for alcohol were:

- Tajikistan,

- Georgia,

- Turkey,

- Kyrgyzstan, and

- Albania.

The effect of equalization

The 40,033 and 132,906 potentially averted deaths in Scenarios 1 and 2 correspond to 7.29% and 24.19% of the total number of alcohol-attributable deaths, respectively.

The difference between the two scenarios is that equalisation results in much higher tax shares overall. A minimum tax share of 25% without equalisation increases the tax shares of all beverage types to 25% in most countries, resulting in an average tax share of 29.06% (the difference to 25% is due to instances where some countries had already had higher tax shares for some beverage types). However, if the price per unit of pure alcohol is equalised for all beverage types, a minimum tax share of 15% leads to an average tax share of 45.28%. The reason for this is the higher non-tax components for wine (i.e., higher production, transport, and trading costs) compared to other beverages, especially spirits.

Alcohol taxation and prevention of death and disease

In all jurisdictions, the category with the highest numbers of deaths averted was either the rest category of “other disease”, mainly made up of alcohol use disorders, or cardiovascular disease (including alcoholic cardiomyopathy), but the ranking of the other categories differed by region.

The five largest groups of causes of alcohol-attributable deaths made up more than 90% of the causes averted in each region:

- cancers,

- cardiovascular deaths,

- gastrointestinal deaths (mainly liver cirrhosis),

- injuries, and

- alcohol use disorders.

Of these, liver cirrhosis and alcohol use disorders have the highest alcohol-attributable fractions, whereas alcohol use is one of many-contributing causes in the larger cause-of-death categories of cancer and cardiovascular disease.

Added value of this study

The researchers examine the current forms of alcohol taxation, and the excise tax share of alcohol prices in the WHO European Region.

Overall, the tax share in this region is low, especially for wine.

- Increasing the tax share to a minimum of 25%, which corresponds to one third of the WHO-recommended tax share of cigarettes, could avert 40,000 deaths in one calendar year.

- A minimum excise tax share level of 15% and ensuring that the price per unit of ethanol (e.g., for a standard alcoholic drink) could avert more than 130,000 deaths annually.

Sensitivity analyses with different price elasticities corroborated the overall potential of taxation policies to improve public health.

This study is the first comprehensive overview of the current state of alcohol taxation implementation for the WHO European Region, highlighting the untapped potential of tax measures to benefit public health.

Despite the fact that alcohol is a psychoactive substance and a known carcinogen, which causes substantial harms to alcohol users, their families, communities, as well as societies and economies in general, it is far less regulated than tobacco or any other psychoactive substance, including the regulations of the level of taxation.

For instance, the WHO recommends that for tobacco the proportion of tax should represent at least 75% of the retail price of the most popular brand of cigarettes. In the WHO European Region, more than half of the Member States follow this recommendation.

However, no such WHO recommendation exists for alcohol and the modelling exercises suggest that alcohol taxation should be considered a priority for public health given the substantial number of lives potentially saved, especially given that pricing policies remain the most under-utilized of all available policy options to reduce alcohol consumption and harms.

Big Alcohol as obstacle to public health oriented alcohol taxation

The WHO European Region is the region where the majority of international alcohol producers are located, which may explain its low alcohol taxation share.

Raising alcohol taxes is a powerful tool to counteract mortality harm caused by alcohol use, as the analyses have shown, and is a tool which has clearly not been used to its full potential in the WHO European Region. For example, the absence of any tax rate for wine in almost half of the countries (most of them EU countries), and the median tax share of <1% for wine for the entire Region, is unacceptable from a public health standpoint.

This is exacerbated by the EU’s longstanding financial support for the wine industry, where it is estimated that from 2007 to 2012 every litre of wine produced in the EU was supported by 0.15 EUR.

Treating Big Alcohol and alcohol policy development with the same approach as to Big Tobacco and tobacco control

Alcohol, like tobacco, is not an ordinary commodity, and thus it should be treated differently from other commodities in public policies. This includes taxation based on public health goals. Developing and establishing a minimum recommended level of tax in the final consumer price of alcohol, following the example of tobacco, is an important step in establishing an implementation framework for alcohol taxes based on these principles. The full potential of taxation increases to reduce alcohol use and the alcohol burden is far from being realized in the WHO European Region.

The gap in regulation and risk awareness between alcohol and tobacco is enormous. With the adoption of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) in May 2003, the tobacco epidemic was globally recognized as a health, economic, and development issue and subsequent measures similar to this legally binding treaty have followed, decreasing tobacco use and its burden worldwide.

Compared to the tax share of tobacco, the average tax share of alcohol prices for the European Region is about four times lower.

While tobacco taxes are clearly seen as health taxes to be levied on products that have negative public health impacts, alcohol taxes have historically been seen as a fiscal measure first and foremost, even in countries that have considerably increased their alcohol tax rates in the past years.

Economic benefits of alcohol taxation

Excise taxation is not only potentially relevant for public health, it also has the potential to increase state revenue. For instance, the recent substantial increase of excise taxation in Lithuania by more than 100% for beer and wine, and over 20% for spirits, resulted not only in decreases in both alcohol consumption and mortality, but also in an increase in tax revenue.

Also, a recent review showed that taxation increases in several countries – contrary to the claims of the alcohol industry – did not result in increases in unrecorded consumption, or a net increase in overall alcohol use, or in alcohol harm. At the same, if a minimum excise tax share for alcoholic beverages were to be implemented, this should be done in conjunction with measures against unrecorded consumption in countries where such increases are anticipated.

Towards a paradigm shift

A paradigm shift for alcohol taxation is clearly warranted and needed. Alcohol taxes should be a public health prerogative, to be implemented as part of a comprehensive policy intervention package and within a global framework convention to overcome the known implementation challenges at the national level.

Alcohol taxes should be considered to be health taxes, and thus viewed as an investment, not a burden. Investing in health was not only critical during the recent COVID pandemic, it will be even more important as part of a “building back better” approach for a sustainable and more resilient economic recovery.

Implications of all the available evidence

Increasing alcohol taxes would bring significant public health benefits. The share of excise taxes on the price of alcoholic beverages should be regularly monitored and the WHO European Region should promote alcohol taxation reforms that would increase tax share, and provide guidance regarding a minimum tax share and an appropriate tax design for maximising public health impact.

Alcohol is very affordable in the WHO European Region, and in many of its countries, taxation has a limited impact on retail prices. There is significant scope for alcohol taxes to play a larger role in raising the prices of alcohol beverages and thereby preventing and reducing alcohol harms.