How Are the Links between Alcohol Consumption and Breast Cancer Portrayed in Australian Newspapers?: A Paired Thematic and Framing Media Analysis

Research article

Abstract

A dose-dependent relationship between alcohol consumption and increased breast cancer risk is well established, even at low levels of consumption. Australian women in midlife (45–64 years) are at highest lifetime risk for developing breast cancer but demonstrate low awareness of this link.

The researchers explore women’s exposure to messages about alcohol and breast cancer in Australian print media in the period 2002–2018.

Methods

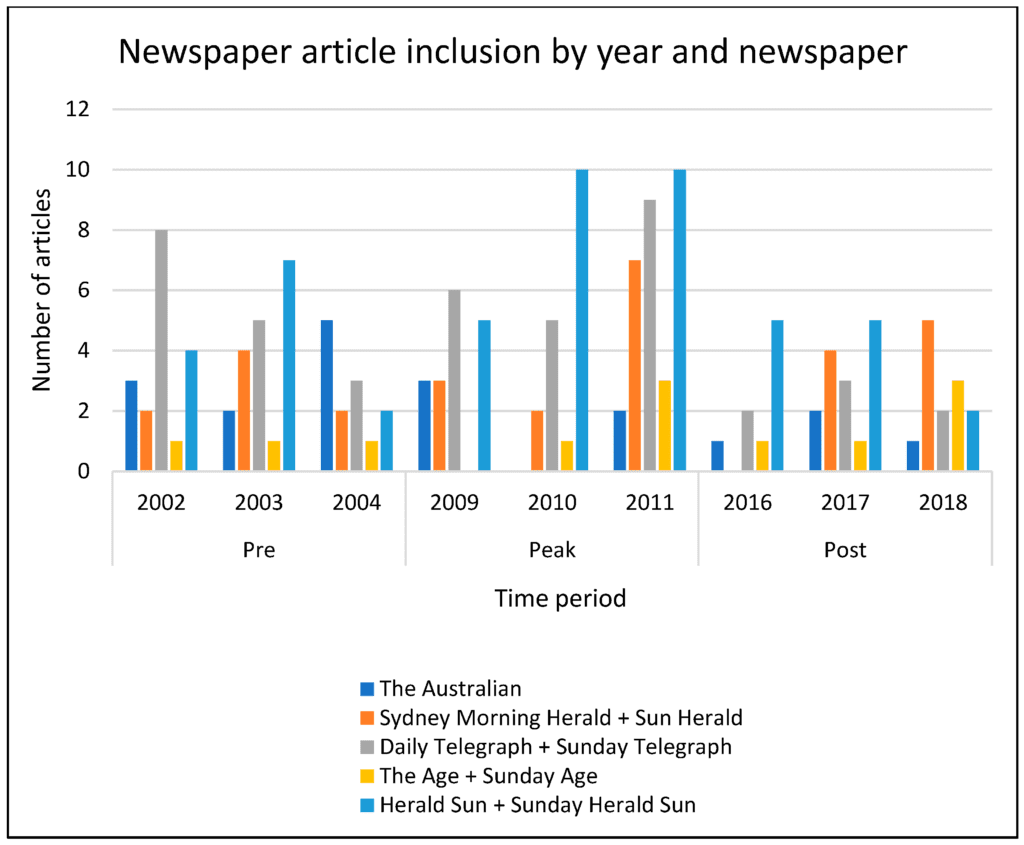

Paired thematic and framing analyses were undertaken of Australian print media from three time-defined subsamples: 2002–2004, 2009–2011, and 2016–2018.

Results

Five key themes arose from the thematic framing analysis:

- Ascribing Blame,

- Individual Responsibility,

- Cultural Entrenchment,

- False Equilibrium, and

- Recognition of Population Impact.

The framing analysis showed that the alcohol–breast cancer link was predominantly framed as a behavioural concern, neglecting medical and societal frames.

Discussion

The researchers explore the representations of the alcohol and breast cancer risk relationship.

The researchers found their portrayal to be conflicting and unbalanced at times and tended to emphasise individual choice and responsibility in modifying health behaviours.

The researchers argue that key stakeholders including government, public health, and media should accept shared responsibility for increasing awareness of the alcohol–breast cancer link and invite media advocates to assist with brokering correct public health information.

Results of the Thematic Analysis

The thematic analysis revealed five key themes present to varying degrees across the three time periods. The most prominent themes – Individual Responsibility and False Equilibrium – were strongly positioned in each time frame. Meanwhile, the themes Ascribing Blame, Cultural Entrenchment, and Recognition of Population Impact were more subtly portrayed during the pre-period (2002–2004) but became more apparent during the peak (2009–2011) and post- (2016–2018) periods.

An important finding was that in in the period 2002–2004, the benefits of alcohol to health were quite prominently featured, whereas in in the period 2016–2018, any such benefits were portrayed as ‘not worth the potential risk of developing breast cancer’.

Ascribing Blame

Over the years, newspapers portrayed the relationship between alcohol consumption and breast cancer as inherently an individual ‘female’ problem. Breast cancer, resulting from alcohol consumption was identified as an outcome associated with being of the female sex. The choices females made and the interactions of these decisions (for example, to bear children, or breastfeed) with their unique biological design were ‘blamed’ for increased breast cancer incidences.

She said drinking had contributed to rising numbers of breast cancer cases, although other factors such as the trend for women to remain childless or have smaller numbers of children and not breastfeed had probably had a bigger effect

(Daily Telegraph, 14 November 2002).

The impact of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in the alcohol–breast cancer risk mix was often reported during this time:

But women whose mothers or sisters had breast cancer, or those taking post-menopausal oestrogen replacement, are at greater risk from alcohol

(Herald Sun, 30 August 2004).

By 2016–2018, the focus shifted from the agency of older women and those of child-bearing age to young females prior to their first pregnancy:

Young women who drink alcohol before their first pregnancy face a 35 per cent higher risk of developing breast cancer, new research suggests

(Daily Telegraph, and Herald Sun, 21 October 2016).

Consistent across time periods was the focus on biology and the interaction of alcohol with female hormones (oestrogen) as well as a focus on post-menopausal females who were considered at higher risk of breast cancer from alcohol consumption:

Other risks for post-menopausal women were: obesity after menopause, as estrogen after menopause is produced in fat cells, alcohol consumption, some risk for those that were non-identical twins and some risk for those with a family history of breast cancer

(Sunday Herald Sun, 6 April 2003).

Experts aren’t clear on why alcohol increases the risk of breast cancer. One theory is that alcohol increases the levels of oestrogen in the blood, which is a risk factor for developing breast cancer

(The Australian, 9 June 2017).

By presenting females as actively making choices related to childbearing, breastfeeding and hormone treatment, these articles tended to isolate inherent female factors and ascribe a level of blame to females for the increase in alcohol-related breast cancer incidence.

Individual Responsibility

Newspaper content from 2009 onwards changed focus from female biological mechanisms to addressing the risk of alcohol consumption behaviours with responsibility for adhering to cancer prevention recommendations positioned within individuals’ control. Although this theme was present across all three time periods, it was most prominent in the articles from 2009 onwards. Alcohol was portrayed as a ‘dangerous’ substance and women were warned to be wary of consuming it. However, the risk alcohol posed in relation to breast cancer was consistently described as modifiable, with individual choice and responsibility highlighted. Women were urged to make necessary changes to reduce their risk:

Women should still remain more wary than men when it comes to drinking, however, and not just because of their smaller body size

(Sunday Herald Sun, 16 November 2003).

“You might not be able to help your genes but you can make lifestyle choices.”

(Sydney Morning Herald, 2 May 2009).

Newspaper content that contained recommendations for breast cancer prevention similarly focused on modifying individual behaviours. However, the suggestions provided were often non-specific (e.g., ‘reduce your intake’), and conflicted with previous articles and/or the alcohol use guidelines at the time (e.g., ‘consume no more than one standard drink’ when guidelines and articles cite two standard drinks), or were vague, including non-standard units of alcohol measurement (e.g., ‘more than the equivalent of half a bottle of wine a week’). Therefore, the implications of different patterns and levels of alcohol consumption in relation to breast cancer risk were unclear:

Heavy alcohol consumption is particularly dangerous, with women drinking more than a bottle of wine a day at 40 to 50 per cent higher risk of the disease

(Daily Telegraph, 14 November 2003).

Even women who had three to six drinks a week had a 15 per cent increased risk of breast cancer compared with non-drinkers

(The Australian, 26 November 2011).

This amount of alcohol was equivalent to three teaspoons of wine per day, she added

(Herald Sun, 4 May 2017).

It was not until 2016–2018 that a slight shift toward population-level recommendations was observed in how the newspapers portrayed the alcohol–breast cancer link (described in the Recognition of Population Impact theme below). In the period 2016–2018, articles acknowledged that the public may be less familiar, if not ‘ignorant’ of the relationship between alcohol consumption and breast cancer:

The findings are likely to come as a surprise to many Australians, who are well versed on the dangers of tobacco, but remain ignorant of alcohol’s link to mouth, throat, stomach, bowel, breast and liver cancer

(Sydney Morning Herald, 14 July 2018).

Within newspaper content from each period, the individual was positioned as an informed decision maker about this relationship:

“It’s about informing them so they can make informed choices.”

(Daily Telegraph, 1 December 2004).

“You should certainly be aware of the information available to make an informed decision and, if you do drink, do so in moderation.”

(Daily Telegraph and Herald Sun, 4 February 2017).

Cultural Entrenchment

Newspaper discussion in all periods placed a level of accountability for the increase in alcohol-related breast cancers on cultural values which encouraged and normalised alcohol use. Modern and more affluent ‘lifestyles’ were specifically criticised in newspaper reports and blamed for the harm alcohol consumption contributes to increased breast cancer prevalence:

Australia’s middle-class lifestyle could also be contributing to the incidence of some cancers such as breast cancer

(The Australian, 15 December 2004).

Modern lifestyles which feature regular drinking, lack of exercise and increased obesity are fueling the disease’s rise, the European Breast Cancer Conference heard

(Daily Telegraph, 27 March 2010).

From 2009–2011 onwards, abstinence was portrayed as an unreasonable expectation due to how deeply entrenched alcohol is in women’s everyday lives:

Alcohol is often part of everyday life, and it can be hard to avoid it completely

(Sunday Telegraph and Sunday Herald Sun, 24 January 2010).

It’s unrealistic to recommend to patients that they completely abstain from alcohol

(The Australian, 9 June 2017).

Consequently, alcohol-related breast cancers were initially portrayed as attributable to a lifestyle which promotes consumption (2002–2004 and 2009–2011) but from 2009–2011 onwards, lifestyles featuring alcohol were presented as unavoidable considering cultural drivers to consume.

False Equilibrium: Alcohol as Tonic and Poison

Alcohol was portrayed as both a ‘tonic’ and ‘poison’ in all time periods, possessing the dichotomous ability to both protect and harm health. Throughout the period 2002–2004, newspapers portrayed alcohol-related harms/benefits as a counterbalance. Whereby, ‘too much alcohol’ put the alcohol user at risk of breast cancer, while moderate consumption, particularly of good wine, was portrayed as a way to prevent breast cancer, and protect health:

The evidence supports theories that a moderate daily intake of wine helps prevent stroke and heart disease, as well as perhaps diabetes and prostate and breast cancer

(Daily Telegraph, 26 October 2002).

All women can weigh the benefits of drinking alcohol against the slight increased risk of breast cancer

(Sydney Morning Herald, 13 February 2003).

In the period 2002–2004, and to a lesser extent in the period 2009–2011, messages that alcohol consumption might pose risk for breast cancer was presented alongside content which incorrectly claimed the risk could be mitigated through diet modifications, or that any purported health benefits of alcohol outweighed the risk of breast cancer:

The increased danger to individual women, however, is usually outweighed by the significant benefits to cardiovascular health

(The Australian, 16 June 2004).

Eating plenty of folate, a B vitamin found in spinach and broccoli, for example, may reduce the risk of breast cancer associated with alcohol

(Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 2011).

Interestingly, the risk of breast cancer from alcohol consumption was presented in the periods 2002–2004 and 2009–2011 as greater than some medical treatments and served to justify the use of HRT and supplements:

“If you have no symptoms I wouldn’t take it, but the risk of HRT causing breast cancer is really minimal—and people often forget other risk factors such as drinking, or a high fat diet.”

(The Australian, 4 September 2004).

Although combined forms of HRT may slightly increase the chances of breast cancer, the effect is dwarfed by other risk factors, such as obesity, diet and alcohol

(Sydney Morning Herald, 7 February 2009).

In the period 2009–2011, articles about the alcohol–breast cancer link included research findings which claimed the beneficial properties of wine extended beyond prevention to include breast cancer treatment:

Red wine could help women with breast cancer boost the chances of their treatment being successful

(Daily Telegraph, 16 February 2011).

An ingredient in red wine can stop breast cancer cells growing and may combat resistant forms of the disease

(Sunday Herald Sun, 2 October 2011).

While in the periods 2002–2004 and 2009–2011 the benefits of alcohol were portrayed to outweigh the risks of breast cancer if consumed responsibility, reports of alcohol as protective and beneficial to health faded over time. By 2016–2018, the release of key public health publications seemed to have impacted this balance, and alcohol consumption was no longer considered ‘worth the risk’ of breast cancer. In the period 2016–2018, there was only a single mention, and the article concluded that the risks associated with ‘moderate’ alcohol consumption outweighed any purported health benefits:

Is a glass of red wine a day ok? No: This is one “wish list” rule everyone hopes is true. However, health professionals claim benefits in red wine are outnumbered by the negatives in alcohol as a whole. The “red wine is good for you” bandwagon began due to the fact it contains the natural compound resveratrol, which acts like an antioxidant and helps prevent damage to the blood vessels in your heart and reduce your LDL, or bad cholesterol. While this may be true, Australian Medical Association vice-president Dr Tony Bartone says research shows a link to cancer

(Daily Telegraph and Herald Sun, 4 February 2017).

Recognition of Population Impact

From 2009–2011 onwards, there was moderate recognition of the increasing population-level impact of alcohol consumption. Articles drew attention to the association of a ‘common cancer’—breast cancer—to alcohol consumption and noted the substantial influence that alcohol could therefore have on reducing the population-wide alcohol-related breast cancer disease burden:

In Australia, 5000 or 5 per cent of cancers, including one in five breast cancers, are attributable to long-term, chronic drinking

(The Age, 19 September 2011).

Alcohol is estimated to cause more than 1500 cancer deaths in Australia every year, with breast and bowel cancers of particular concern… About 1330 bowel cancers and 830 breast cancers are attributed to alcohol each year in Australia, and it has been estimated about 3 per cent of cancers can be blamed on alcohol consumption each year

(Sydney Morning Herald, 8 September 2017).

In addressing the population impact of alcohol on breast cancer incidence, a small number of newspaper articles presented population-level interventions as appropriate solutions:

The research will help shape future campaigns warning of the risks of drinking. Graphic labelling similar to those displayed on cigarette packs could also be introduced to minimise harmful drinking

(Herald Sun, 20 April 2017).

It may be beneficial for public health authorities to consider guidelines specific for cancer survivors, rather than relying on prevention messaging

(Herald Sun, 4 May 2017).

From the thematic analysis, five themes emerged which presented alcohol as simultaneously harmful and beneficial to breast cancer, as well as deeply embedded in Australian culture, and contributing to a considerable morbidity and mortality burden. Meanwhile, alcohol-related breast cancers were positioned as stemming from inherent female concerns and choices controlled by the individual which were perceived to be the responsibility of the individual to address. Additionally, various conflicting and misleading messages of the potential health harms/risks associated with alcohol consumption were portrayed by newspapers.