Taxation of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages: reviewing the evidence and dispelling the myths

Analysis

Summary box

- Health taxes (on tobacco, alcohol, and SSB) are effective economic instruments to change people’s behaviour and reduce the consumption of unhealthy products.

- The article summarises and critically discusses the large body of evidence regarding the effect of taxes on reducing the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and SSB.

- The article also provides consolidated evidence regarding the lack of economic substance behind common arguments that industries use to oppose these taxes (eg, illicit trade, negative effects on employment, regressivity).

- Evidence provided in this article can be used to design and implement health taxes more effectively.

Abstract

The article reviews the large body of evidence on how taxation affects the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB). There is abundant evidence that demand for tobacco, alcohol, and SSB is price-responsive and that tax changes are quickly passed on to consumers.

This suggests that taxes can be highly effective in changing consumption and reducing the burden of diseases associated with consuming these products.

Tobacco, alcohol, and SSB industries oppose taxation on similar grounds, mostly on the regressivity of taxes since regressive taxes take a larger percentage of income from low income earners than from middle and high income earners; but also on the effects taxes might have on employment and economic activity; and, in the case of tobacco, the effects taxation has on illicit trade.

Contrary to industry arguments, evidence shows that taxation may have short-term negative financial consequences for low-income households. However, medium and long-term financial benefits from reduced healthcare costs, better health, and welfare largely compensate for such consequences.

Moreover, taxation does not negatively affect aggregate economic activity or employment, as consumers switch demand to other products that generate employment and may compensate for any employment loss in taxed sectors.

Evidence also shows the revenues generated are generally spent on labour-intensive services. In the case of illicit trade in tobacco, evidence shows that illicit trade has not increased globally (rather the opposite) despite increases in tobacco taxes. Profit-maximising smugglers increase illicit cigarette prices along with the increases in licit cigarette prices. This implies that even when increased taxes divert some demand to the illicit market, they push prices up in the illicit market, discouraging consumption.

Harm from unhealthy products

Consuming products with significant and negative impacts on health has economic implications. Such consequences can be broadly separated into two groups of costs:

- Direct costs linked to the treatment of diseases; and

- Indirect costs that are linked to premature mortality, loss of productivity due to absenteeism and presentism (ie, people going to their jobs but being less productive because of disabilities, illnesses, etc.), opportunity costs of caregivers, suffering and pain, etc.

Purpose of the study

Fiscal tools, such as taxes, can play a fundamental role in preventing chronic diseases and improving people’s lives and social outcomes.

This article presents current evidence on taxation as a proven tool to discourage the consumption of harmful products (tobacco, alcohol, and SSB) and thereby improve population health.

The study discusses the economic rationale for taxing these products and documents the health effects and costs to society. It presents evidence on the effectiveness of taxation in raising prices and reducing consumption, along with showing how considering health benefits and indirect financial effects, taxation disproportionately benefits poorer households.

The study also considers the role of industries in opposing taxation. The article differs from previous reviews in its scope (covering all three products) and in its comprehensiveness (in addressing the arguments for and against health taxes, including those arguments used by the industry).

Alcohol taxation specific findings

Prevalence of alcohol use

Although the prevalence of current alcohol users aged 15 years and older decreased between 2000 and 2016 (from 47.6% to 43%), the per capita volume of pure alcohol consumed has increased from 5.7 litres to 6.4 litres and is projected to further grow to 7 litres by 2025.

If only alcohol consumers are considered, pure alcohol consumption per capita reached 15.1 litres in 2016 (up from 11.1 litres in 2000). Furthermore, considering global population growth in 2000–2016, the number of alcohol users worldwide increased by 16%.

The amount of pure alcohol consumed globally increased by 58% (an annual average increase of 3.1%.

It has been estimated that the economic cost of tobacco consumption at the global level was equivalent to 1.8% of the world GDP in 2012 (about 1.8 trillion in US dollar purchasing power parities (USD PPP). Of that amount, direct costs (related to healthcare expenditures) totaled USD PPP 467 billion (equivalent to 5.7% of global health expenditures).

Pooled results for 29 locations (countries, states/regions, cities) found that the total cost of alcohol consumption amounted to USD PPP 817 per adult, equivalent to 1.5% of the GDP (of which 68% were indirect costs).

Externalities due to alcohol

The consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and SSB is linked to negative externalities, as such, consumption negatively affects the well-being of third parties (externalities occur when one individual’s action – consumption, production – affects the well-being of another individual).

Not only negative externalities are present in the consumption of these products, but also negative “internalities”, which arise from individuals ignoring or not correctly considering harmful health effects to themselves.

For instance, alcohol externalities involve traffic road accidents, domestic and street violence, etc.

In the case of alcohol, externalities arise from the healthcare costs related to the many conditions caused alcohol. In all cases, family suffering associated with pain and illnesses can also be considered externalities.

Effectiveness of alcohol tax policies to decrease consumption

For alcohol, taxes are fully passed or overshifted.

A review found that taxes are generally overshifted in the case of beer and fully shifted for wine and spirits.

- In the US, state and federal alcohol taxes appear to be overshifted, especially for beer and spirits. The price adjustment is also quite rapid, within 3 months of the tax change.

- For the UK, the pass-through rate varies by the price level of alcohol products, as producers of relatively cheaper alcoholic beverages tend to undershift taxes. In contrast, those of relatively more expensive beverages overshift them.

- A similar finding was reported for the pass-through of alcohol taxes for 27 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

The evidence on own-price elasticity for alcohol is also compelling, with values around −0.5.

However, not all types of alcoholic beverages are equal, as beer demand is less price-responsive than wine and spirits (-0.3 vs −0.6, respectively).

There is little evidence of gender differences in price responsiveness.

Studies show different results on own-price elasticities by age, finding no conclusive differences between youths and adults.

Even binge alcohol users are price-responsive but tend to choose cheaper alcoholic drinks to keep up their alcohol consumption. This implies that policies aiming at increasing the price of more affordable alcoholic drinks (eg, minimum unit price policies) can effectively reduce binge and/or heavy alcohol use.

Finally, evidence on how prices affect alcohol initiation is scarce but suggests that higher prices delay and, to some extent, prevent initiation. This can have long-lasting effects on future alcohol use patterns; for example, individuals who initiate at older ages have a lower probability of having frequent heavy-alcohol consumption episodes.

Challenges from the alcohol (and other health harmful) industry

The tobacco industry has a long and well-researched history of concealing evidence of the toxicity of its products, deceiving the public about the harmful effects of tobacco consumption, and interfering in public policy. As early as the 1950s, the tobacco companies concealed evidence of their products’ harmfulness and nicotine’s addictiveness. In the 1970s and the 1980s, they denied links between smoking and cancers and the harmfulness of secondhand smoking.

More recently, despite robust scientific evidence, they misled the public regarding the relative safety of “light” or “low-tar” cigarettes. The tobacco industry’s tactics have been exposed through successful efforts to make the industry’s documents public. These documents have demonstrated the large discrepancies between what the industry knew and the ideas it promoted.

Apart from concealing and distorting evidence, the tobacco industry has given several arguments to deter, impede or delay increases in tobacco taxes.

The most common and consistent arguments were that tobacco taxes:

- are regressive;

- lead to more illicit trade and foster organised crime; and

- reduce employment and harm businesses.

The tactics of the alcohol and SSB (food, in general) industries to oppose taxes and regulations are remarkably similar to those used by the tobacco industry.

- They also shift blame for unhealthy eating or alcohol harm away from themselves as purveyors of products and onto the individuals who are intentionally influenced by marketing campaigns.

- The alcohol and processed food industries have also linked regulations and taxes to the loss of personal freedoms.

- Self-regulation is often proposed as an effective and more efficient alternative to state regulations even when this has been shown to be ineffective.

Like the tobacco industry, the producers of alcohol and SSB lobby governments and the public by arguing that taxes do not reduce consumption; that they are regressive; and that they are “discriminatory” (as they are levied on specific groups of products) or even unconstitutional.

Debunking the regressivity of alcohol taxes claim

Common arguments from tobacco, alcohol, and SSB industries claim that because poorer individuals spend more on these products as a proportion of their budget, any price increase induced by tax changes will affect them disproportionally more than, for instance, richer individuals. Hence, these taxes are regressive.

However, tobacco, alcohol, and SSB are unlike other taxable goods.

Preventing health and economic harms associated with consuming alcohol generates large benefits to current and potential consumers.

These benefits are:

- Health improvements,

- Healthcare cost reductions, and

- Higher disposable income for purchasing non-toxic goods and services.

Moreover, the financial impact of these prevented costs is disproportionally higher for poorer households, and they more than offset any negative immediate financial costs that taxation may have on them.

Several studies have been conducted using the extended cost-benefit analysis (ECBA) methodology to test this hypothesis. ECBA incorporates any short-term welfare losses from excise taxes into a framework that includes medium- and long-term health benefits for those who quit or consume fewer harmful products. Among other aspects, it accounts for differential behavioural responses across population groups—including different income groups—by estimating specific group price elasticities.

A recent ECBA in Brazil shows that price increases on alcohol, tobacco, and SSB have positive and progressive effects when incorporating the impact of health taxes on prices, medical expenditures, and productive lives.

A recent report analysed the distributional effect of alcohol taxes in the UK, finding no evidence to support the idea that alcohol taxes are regressive.

Furthermore, once the use of alcohol tax revenues by the Government is considered, results can be strongly progressive if revenues are used to finance increased health or other pro-poor programmes.

Note that “soft” earmarking (ie, that which is not legally required) helps overcome political opposition to higher tobacco excise taxes. The same effect can be found for SSB taxes: in the case of the Philadelphia SSB tax, for instance, a significant proportion of revenues were allocated to fund preschool education and community schools.

In the case of alcohol, the relative financial burden may be affected not only by income but also, crucially, by the intensity of alcohol use. In Australia, alcohol taxes represent a higher burden to heavy alcohol users, irrespective of their incomes. Because of that, Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) policies or taxes that increase the cost of the cheapest alcohol can be more effective in reducing alcohol consumption without having highly regressive effects. However, this partial study does not consider the distributional impact on revenues and healthcare cost savings.

Debunking the illicit trade claim

One of the common arguments the tobacco and alcohol industries have used to challenge health taxes is to claim that these policies will be ineffective because they will encourage illicit trade.

While illicit trade can undercut prices in the market, there is little evidence that it has undermined the effectiveness of taxes in raising overall prices.

For alcohol, there is less evidence of a relationship between taxation and illicit, unrecorded alcohol consumption. Unlike tobacco, alcohol is less susceptible to smuggling because it is heavier and more difficult to transport relative to its value. On the other hand, opportunities for artisanal, informal production are more widespread.

WHO estimates show that the global share of unrecorded alcohol consumption fell from 28.6% in 2005 to 25.5% in 2016. Estimates of such a share for low- and lower-middle-income countries is around 43% for 2016, while for upper-middle and high-income countries, it is about 17.5%.

Large variations also exist by region.

Increases in small-scale purchases of untaxed products (eg, bootlegging, cross-border shopping, etc.) have also been blamed as consequences of higher taxes and as reasons behind the failure of taxes to curb consumption. Evidence on sub-national SSB taxes for some US counties shows that, for instance, cross-border shopping exists but is not enough to offset the decreases in consumption that taxes produce. There is also evidence that the effect on aggregate consumption is small for alcohol and tobacco and it fades with distance from the border.

Debunking the economic activity and employment claim

According to the tobacco, alcohol, and SSB industries, excise taxes on these products reduce economic activity and employment when people purchase less of them.

This claim contradicts their talking point that taxes do not have an impact on consumption,

The claim is also simplistic and untrue.

When taxes reduce the consumption of these products, it can affect sales and employment in those sectors. However, consumer spending on other products will increase and raise sales and employment in those other sectors.

Furthermore, when governments spend the excise tax revenues, they also generate employment. Studies have found that shifting demand from the tobacco industry which is relatively capital-intensive to industries that are more labour-intensive can actually increase employment.

In the case of alcohol, a study simulated the effect of an alcohol tax increase on employment in six states and found that such a tax would have a positive impact on employment, mostly because the resulting fiscal expenditures would spur greater economic activity.

Conclusions

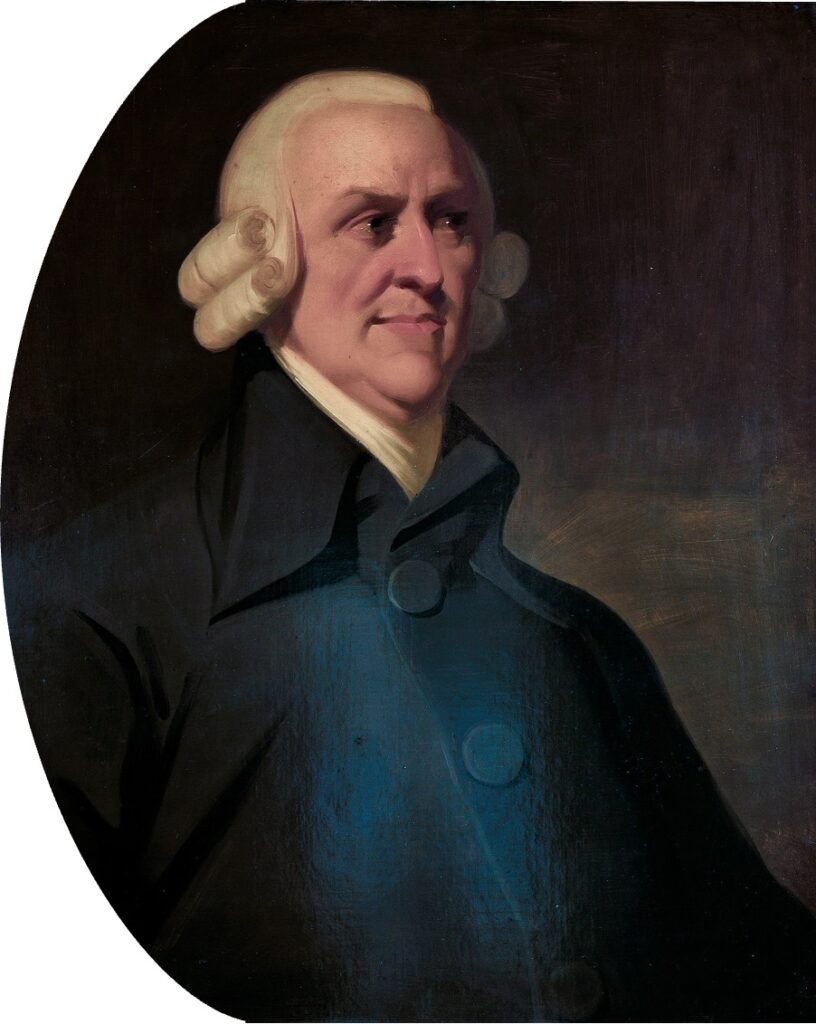

In 1776, Adam Smith stated:

Sugar, rum, and tobacco are commodities which are nowhere necessaries of life, which have become objects of almost universal consumption, and which are therefore extremely proper subjects of taxation.”

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776

Much time has passed since then and evidence on the negative effects of the consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and SSB is overwhelming (something unknown when Smith made that statement).

In addition, economic theory has demonstrated that taxing products that generate negative externalities not only increases revenues but also increases economic efficiency.

Evidence collected over the past decades also shows that alcohol taxation is the single most effective intervention to curb alcohol use and harm.

WHO has included alcohol taxes as a “best buy” (interventions with the highest cost-effectiveness) to reduce consumption and the burden of diseases linked with its use.

Reducing consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and SSB and the burden of disease associated with them is not only about reducing healthcare costs, which can be significant and put great pressure on health systems.

It is also about increasing the social return on human capital.

Chronic illnesses and conditions associated with the consumption of these products hinder individuals’ productive performance (due to absenteeism and presentism – reduction of productivity at work due to illnesses).

Premature mortality implies that social resources devoted to, for instance, education and health, are not fully realised and are prematurely lost.

Loss of income due to illness and mortality may affect households’ present and future well-being, creating a vicious cycle of lower human capital investment and poverty.

Taxes are an important element of broader efforts to reduce consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and SSB. They are not a cure-all. They should be used along with other cost-effective measures.

These measures include mass media education campaigns, bans on smoking or alcohol use in public places, prominent labelling showing adverse health effects (especially for tobacco and alcohol); restrictions on opening times (for alcohol); etc.

There is enough evidence on the effectiveness of these measures to amply justify their implementation, with adaptation and prioritisation depending on individual country circumstances.