The Sustainable Development Goals should be reset to prioritize poverty, health and climate

Comment

What past research says

The SDG era started with big goals but is struggling to achieve significant progress. Past research recognizes that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set high expectations. They were meant to tackle a wide range of global challenges, from poverty and health to environmental protection and fairness.

Stance of present research

Nevertheless, present research admits that the world has not made as much progress as was hoped for with the SDGs.

Out of the 140 specific targets that were set, only about 15% are currently on track to be achieved. It implies that authorities are falling behind in reaching most of these goals.

The research also points out that there isn’t a unified worldwide effort to fix problems of health, inequality, and the environment.

What the present paper adds

This present paper contributes by highlighting that the world has entered an era of “health uncertainty” due to various crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and societal transformations.

This is due to a shift from sudden crises to long-lasting and complex uncertainties worldwide. This is noticeable through events like the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing divisions in societies, and the challenges linked to climate change.

The present paper argues that mere adjustments to individual SDG targets are insufficient. It underlines the need for a reform of the SDGs.

The health uncertainty complex

It is not clear that a rescue operation for the SDGs would improve global health. The most recent Human Development Report suggests that the world has changed too much to continue with the SDGs as they are. It proposes that the world is caught in a new ‘uncertainty complex’ with “acute crises giving way to chronic, layered, interacting uncertainties at a global scale, painting a picture of uncertain times and unsettled lives”.

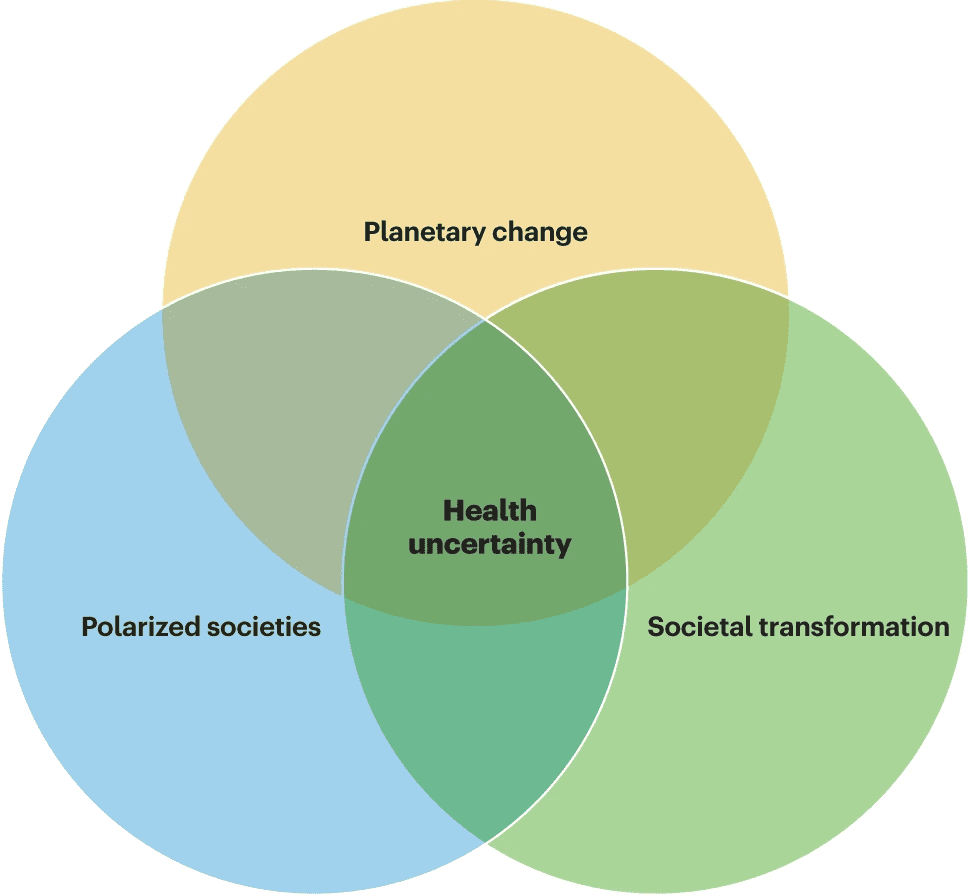

The report describes the world as being caught in three volatile crosscurrents (Fig.1):

- the dangerous planetary changes of the Anthropocene, including climate change;

- the pursuit of sweeping societal transformations on par with the Industrial Revolution; and

- the vagaries and vacillations of polarized societies.

COVID-19 has shown the extent to which health has become an integral dimension, and sometimes driver, of this uncertainty complex, becoming highly politicized in the process. This health uncertainty demands new approaches, but the political system does not seem to be ready for them.

The Ebola outbreak that hit three West African states in 2014 and was still raging during the SDG negotiations in 2015 was a foreshadowing of the health uncertainty that was to come. During the High-Level Meeting on universal health coverage in New York in September 2019, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board issued its first report, “A World at Risk”. This warned of the high probability of a pandemic, but did not spark much interest, despite the inclusion of ‘global health risks’ in Target 3.d of SDG 3. SARS-CoV-2 struck the world just 3 months later. The virus could only have such a drastic impact because of persisting inequalities, corporate greed, ongoing social polarizations, lack of global solidarity and lack of progress on universal health coverage. The COVID-19 pandemic led to the realization that a health crisis can easily become a polycrisis “where disparate crises interact such that the overall impact far exceeds the sum of each part”.

Nobody expected that a pandemic, with its many repercussions, would stop SDG progress in its tracks. But even more, nobody would have envisaged that so little would be done to ensure that a similar tragedy would not strike again. In a period of uncertainty, defined by the ongoing polycrisis, the adjustment of individual SDG targets is not enough. Dysfunctionalities should be used productively to create new systems. To move forward with real change, four issues that have troubled the SDGs need to be addressed.

Four key reform areas

This study emphasizes a new era of “health uncertainty” marked by crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and societal shifts. These challenges have transitioned from sudden crises to ongoing, complex issues. Mere adjustments to SDG targets are insufficient.

This is why the study proposes four key areas for reform: Promoting a well-being economy, recognizing power inequalities, prioritizing planetary health, and reforming global financing.

- Well-being for everyone

- Initially, the SDGs focused a lot on making countries richer, but they didn’t pay enough attention to fairness and inequality.

- More focus on how money is shared, how trade works, and why some people are rich while others are poor.

- Move towards an economy that cares about everyone’s well-being and the planet.

- Understand that some have more power (Power Dynamics)

- When we measure how well countries are doing with the SDGs, we should think about who has more power.

- Sometimes, rich countries get good scores, even if they cause problems for poorer countries.

- The need to come up with a new way to measure that do not neglect these differences.

- Take care of planet’s health

- At first, the SDGs assumed that we had 15 years to make things better. But now, planet’s health is in danger.

- Climate change are big threats to health.

- Change how money works around the world

- To make progress on things like ending poverty, improving health, and dealing with climate change, we need money.

- But we have to change how money works globally.

- Some ideas are to provide emergency money, give more loans to governments, and create new ways to pay for climate projects.

Promote the well-being economy

The central constructional flaw of the SDGs must be addressed: the equation of prosperity with growth in gross domestic product (GDP) and the ensuing neglect of equity.

A new value-based narrative will be essential, such as that presented by proponents of a well-being economy and the World Health Organization (WHO) Council on the Economics of Health for All.

The SDGs were constructed assuming unjustifiable certainty in relation to the continuation of existing models of growth and development, the positive dynamics of globalization and economic liberalization, the functioning and acceptance of the existing multilateral order, and the hegemony of the global north.

The SDGs do not adequately address the underlying systemic inequities and uncertainties that perpetuate poverty, inequality, climate disasters, and health disparities.

Structural factors such as wealth distribution, trade regimes, social determinants of health, food price speculation, gender discrimination, and economic inequalities must be addressed. There is a lack of fiscal space for investing in health, including intellectual property, lack of access to medicines, lack of technology sharing, and inequitable distribution of production sites. The well-being of people and the planet should be addressed in a coordinated fashion through approaches such as One Health and Planetary Health.

Context of this paper: how to increase fiscal space and accelerate SDGs progress

A landmark analysis by the Copenhagen Consensus Center showed in 2023 how alcohol policy can help increase fiscal space, reduce costs and harm from alcohol, and promote progress towards multiple SDGs.

2023 Study by Copenhagen Consensus Center: Alcohol taxation among 12 most efficient ways to eradicate poverty, promote Development

The study has identified 30 cost-effective interventions to achieve the SDGs in the fastest way possible. Among these interventions, alcohol policy and especially alcohol taxation have been ranked as the second and third most effective intersectoral policies.

Researchers of the Copenhagen Consensus Center examined the benefit-cost analyses of various NCD interventions in low-income (LICs) and lower–middle–income (LMCs) countries. The analyzed 30 interventions recommended by the Disease Control Priorities Project, including six intersectoral policies, such as taxes and 24 clinical services. Using a previously published model to estimate intervention costs and benefits through 2030, researchers found that intersectoral policies often provided great value for money.

They conclude that there are several cost-beneficial opportunities to tackle NCDs in LICs and LMCs. In countries with very limited resources, the best-investment interventions could begin to address the major NCD risk factors, especially tobacco and alcohol, and build greater health system capacity, with benefits continuing to accrue beyond 2030.

Improving alcohol policies could reduce overall alcohol consumption and avert 150,000 deaths over the rest of the decade until 2030.

Each dollar spent on alcohol policy development will deliver $76 of social benefits.

An alcohol tax increase alone can generate large, if slightly lower, benefits at $53 back on the dollar.

Alcohol contributes to a large number of diseases and causes an additional 700,000 accidental deaths globally, as well as immense social damage.

Alcohol has a negative impact on sustainable human development, hindering progress in 14 out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It affects all three dimensions of development, including economic, social, and environmental aspects, and permeates through all aspects of society.

And poverty is in many ways – at least 7 – connected to alcohol and impacts all levels from individuals and families to communities and societies in general.

This indicates that addressing alcohol-related harms is crucial for achieving sustainable development.